Intimations of war and the bill for a Brick Lane curry. Queer kisses, shamanistic gurgling, miles of VHS tape and lasers in the jungle. This year’s Turner prize exhibition opens this Saturday at Cartwright Hall in Bradford, the current UK city of culture.

A soundtrack of a 16th-century Lutheran hymn and peals of church bells create an unresolvable conflict with the small photographs trapped behind glass on a low shelf in Rene Matić’s installation. The voices of Nina Simone and bell hooks are dragged from the ether, along with the chants of trans rights activists and commuters calling for a free Palestine. Rihanna sings Lift Me Up a cappella as I go from snapshot to snapshot, looking for the story amid the club scenes and marches, the street graffiti and a baby in a bath. Here’s an elderly man in hospital, then lipstick and cigarettes and a page from a remembrance book: “Dad, Our Hero, VIP, Legend” reads the dedication.

All these scenes, I take it, are from Matić’s life. It is all a mix of the personal and the political. I think of Nan Goldin and of a life being lived and documented. The artist, 28, displays their affinities in an installation that feels at once rich and sparse, restrained and confessional.

Behind me, a huge printed cotton drop-cloth sags in space, as if it has run out of energy, or belief, or something. NO PLACE reads one side, FOR VIOLENCE, the other. Although repeating the calls for peace in response to the assassination attempt on Donald Trump’s life while he was on the campaign trail in 2024, there’s more than one way to read the banner. The private and the public, what’s background and what is foreground in the mixed race, gender fluid, working-class artist’s life? Peace and protest, friendship and family are all mixed together, along with contested ideas of nationhood and belonging. And what of Matić’s collection of black dolls, staring from their shelves, set into a pinkish brown wall? It all adds up to a frozen autobiographical tableau, suspended and ambiguous, like that banner, caught in the middle of things.

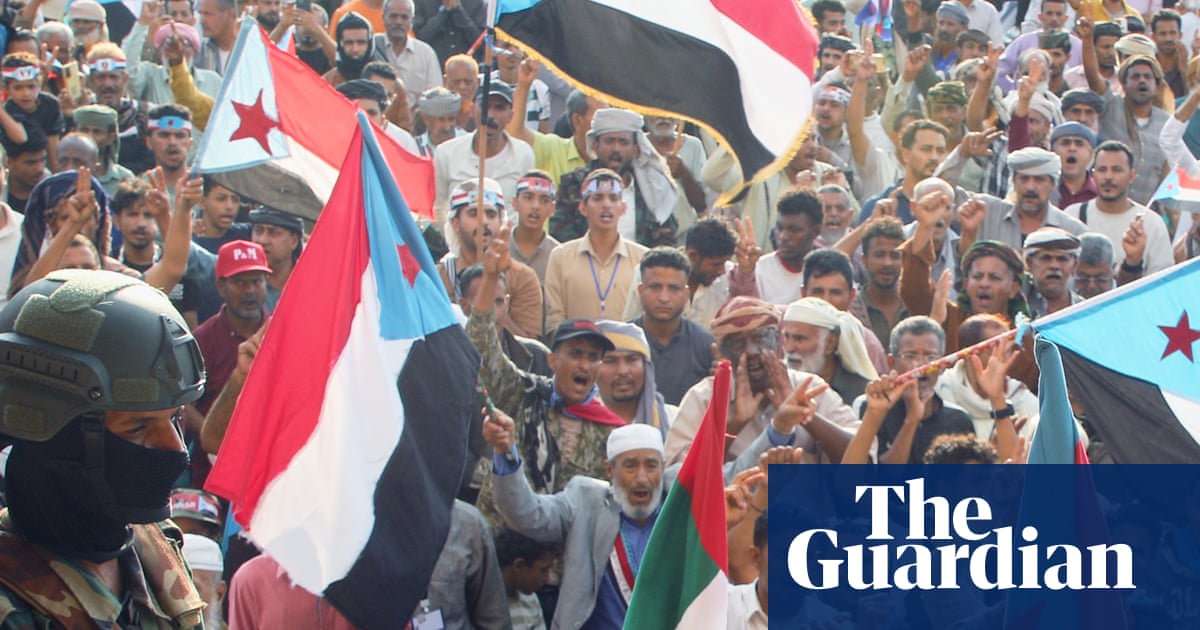

Equally unsettling and deliberately ambiguous, Mohammed Sami’s paintings intimate violence. Broken crockery under an exploding sky. Clothing suspended in water, like the last view of someone drowning in a tank. A horseshoe-scuffed and trampled patch of ground where something or someone has been dragged from a field of sunflowers. A vast panoramic view of wind-thrashed palms in an orange haze, where green lasers blitz the undergrowth. It’s like a frozen screen in a stalled video game.

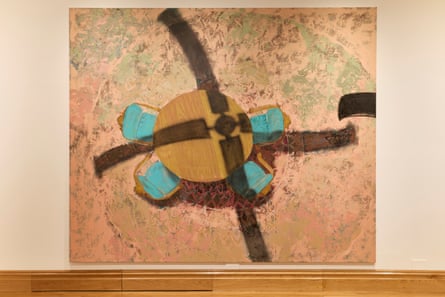

An abandoned table and chairs are caught by a surveillance camera overhead, the view obstructed by the menacing shadow of a thwapping ceiling fan. Sami showed several of these heavily worked canvases last year, hung among the old masters and heirlooms at Blenheim Palace, a collision of past imperial might and modern violence, by an artist who began his career painting official portraits of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad.

Sami always been good, like Luc Tuymans, at intimating catastrophe and violence in his unpeopled paintings, but it strikes me that his recent work has become technically a lot more tricksy, in the manner of Anselm Kiefer and Miquel Barceló. All that painterly heavy breathing gets in the way, and the more Sami does, the less I believe in it.

Here come sounds again. This time, tinkling bells, whale song and radiophonic whoops, wind-chimes and the insistent warble of an old telephone. I was backing out of Vancouver-born Korean artist Zadie Xa’s installation even as I shuffled across the shiny gold metallic floor in my specially provided overshoes, so as not to spoil the perfect sheen. The sounds all emanate from dangling giant artificial seashells. Undersea light drifts across the walls and tiny shamanic bells hang in a conch-like spiral over an octagonal dais shimmering with rainbow reflections, the whole thing mirrored in the floor under my feet.

The paintings that line the walls are rife with folkloric Korean figures, skeletal musicians, swimming dolphins, passing squid and sea-turtles. This woozy, overwrought and overthought exercise in luxury brand shamanism is as excessive as it is unnecessary. The title, Moonlit Confessions Across Deep Sea Echoes: Your Ancestors Are Whales, and Earth Remembers Everything, says it all.

Everybody’s got a spiel nowadays, and Xa’s is particularly unctuous. Everyone also has a story, as if that might explain everything. Ten large sculptures hang in space, melding and separating as you move around and between them. Nnena Kalu works by repetitive binding and wrapping, knotting and furling, layer on layer, working on simple armatures with adhesive tapes, clingfilm, repurposed plastics, fabrics, cable ties, VHS tape, cardboard and spillage of manufactured, spun and extruded materials. Her additive, repetitive process depends on the artist’s reach, her concentration and persistence. Her sculptures are always the same and always different. They rise above us, reaching out or snarling in on themselves. They’re bound and unbound and filled with variety. These embodied forms have a complex physicality. I think of heads and torsos, arses, necks, bellies and manes, the human and the animal. They bulk and extrude, twist and float.

People often talk of this or that artist being a force of nature, and of being driven. Neither artistic gifts nor disabilities are to be dismissed, as necessary as they are a hindrance. Born in Glasgow in 1966 Kalu is an autistic, learning disabled artist with limited verbal communication. Supported by visual arts organisation Actionspace, Kalu’s primary assistant, Charlotte Hollinshead, has worked with her since 1999, and describes her role as “a glorified assistant”, insisting that Kalu has total control of her art.

Her work is irreducible. There’s a horizon to what we can know. Kalu’s sculptures have been compared to Phyllida Barlow and the fibre art of Sheila Hicks. One might also think of the complex, many-layered sculptures of American artist Judith Scott (1943-2005), who also worked with severe physical and mental limitations, finding her way after years of institutionalisation and neglect. Repetition and compulsiveness were also at the root of the immense corpus of work made by German artist Hanne Darboven (1941-2009), who worked within rigorous self-imposed systems and constraints.

Kalu works between the elective and the given. This is as true of her drawings as it is of her sculptural works. The repetitive spiralling vortices of her drawings all depend as much on where she leaves off, on their returns and alterations, on flow and variation, as they do on the body transcribing its actions on to paper. They are riotous and rhythmic, purposeful and compelling. There’s no fudging. Kalu deserves to win this year’s Turner prize.

3 months ago

97

3 months ago

97