Justin Goss was in the shower when he first heard the piercing wail of a nearby tsunami early-warning siren. Still dripping wet, he threw on clothes, grabbed his dog and rushed to the truck. The pair made it 3 metres and no further.

“The whole parking lot across the street was jammed up. It was complete gridlock within three minutes,” he says. “I thought, ‘Oh shit, this is not good.’”

In the downtown core of Tofino, a town on Vancouver Island, there are no warning sirens. But word quickly spread that people were fleeing the beaches. Panicked parents rushed to pick up their children from day camps. Restaurants in the Canadian holiday haven emptied.

“We told everyone to get out fast,” remembers Brenna MacPherson. “We didn’t know how bad it was going to be.” Some patrons settled up, others left bills unpaid. Some wandered the street with cocktails in hand.

Residents of this small town have long been braced for a deadly tsunami. When – not if – a tectonic plate snaps upwards, the resulting energy will convert to a wave moving at the speed of an airliner. As it reaches shallow water, it will advance towards the shore at 20 miles an hour (32km/h) – slower than an elite sprinter – but swap speed for size. A wall of water 20 metres (65ft) high is possible when it finally reaches land.

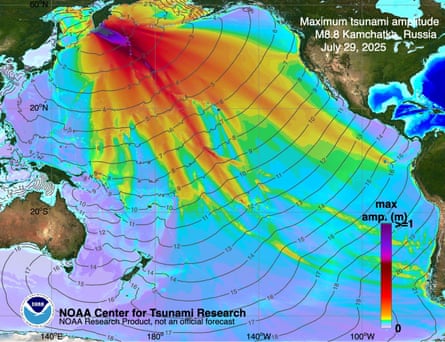

This summer, on 29 July, the powerful but distant Kamchatka earthquake in Russia that triggered sirens in Tofino amounted to little more than an eventual swell against the coast when the wave finally arrived hours later. Still, the false alarm forced residents to confront the town’s precarious geography – and an old question: how do you prepare for a disaster whose timing is completely unknown?

Tofino is a sliver of thick forest flanked by miles of beach that absorbs the full catalogue of the Pacific’s unpredictable moods. It is connected to the rest of Vancouver Island – to food, medicine and fuel – by a single highway riddled with steep gradients, hairpin turns and rockslides.

Roughly 60 miles (100km) offshore, the Juan de Fuca plate slides beneath the North American plate – a slow-motion collision where pressure builds over centuries. When it finally slips, it unleashes a “megathrust” quake. Similar ruptures have struck 19 times over in the past 10,000 years – the last in 1700, when 600 miles of seafloor dropped 20 metres and a massive wave radiated in all directions.

The disaster was captured in the oral history of Indigenous peoples living on Vancouver Island. Villages and forests vanished and rocks from the ocean appeared in lakes. In one Nuu-chah-nulth story, dating back hundreds of years, an orca – K’aka’win – was carried more than a mile from an inlet to Sproat Lake by a tsunami wave. The killer whale survived for nearly a month before it succumbed to the fresh water.

Katsu Goda, a professor at Western University in Ontario who studies catastrophe modelling, recently travelled to Tofino to meet colleagues from Indonesia and Cuba as part of a broader project to develop response plans with local officials.

On the morning of 3 October, nearly 40 people packed into a hotel conference room. At the tables were flood experts, sociologists, hotel managers, town councillors, firefighters and disaster-response staff all tasked with “community asset mapping” – an exercise in which the town’s weaknesses, which impede a speedy response to disaster, are identified.

The room broke out in muffled gasps when the soft-spoken Goda told attenders that an earthquake reaching 9 on the Richter scale was nearly 1,000 times greater than one measuring a 7. And yet when a quake of such a devastating magnitude strikes, officials and first responders have to ignore its effects because of the wave that arrives minutes later, the power of which will depend on tides, storms and whether the quake lifts or drops the land.

An additional issue for Tofino is seasonal crowds. Its bohemian mystique and powerful waves have long been a lure for surfers. Hundreds of thousands of visitors flock to its lowest-lying areas on holiday. Under most earthquake scenarios, when the “big one” strikes, anyone near a beach has about 15 minutes to escape to higher ground. But those minutes are misleading, says Goda.

“You might lose five minutes waiting for aftershocks. If it’s daytime, the journey is far easier than at night. And then you might be ready to leave, but then realise you need to find your kids.”

The town is also vulnerable in other ways. Tofino gets all its drinking water from a nearby island. Climate change is eroding beaches and worsening storms that push water farther inland. “Atmospheric rivers” – the long, narrow areas in the sky that carry most of the water vapour from the tropics – and rockslides can overwhelm the lone highway. Last summer, fires reached perilously close to the road.

And while the lure and promise of artificial intelligence has touched nearly every field, Goda says it remains a costly and impractical tool for those seeking accurate models of tsunamis.

“To make a credible model, we need experience. And we lack the fundamental information because when it comes to tsunami, there is so little good data,” he says.

after newsletter promotion

The only useful data that exists comes from the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan and the 2010 quake in Chile, but neither can come close to accurately modelling what might happen in Tofino.

On Chesterman Beach, one of the town’s most popular spots, waves thunder along the shore and eager surfers throw their bodies into the foamy swell. A storm the day before has piled bull kelp, shells and fresh driftwood on to the shore. Bundled tourists absorb the rugged seascape.

Many visitors know of the possible tsunami – but most also anticipate having about an hour to get to higher ground. And this, for Hilary O’Reilly, is a problem.

As Tofino’s emergency programme coordinator, O’Reilly faces the challenges of educating a community that bulges and shrinks with tourism. She must ensure guests who visit for a weekend getaway are also aware of the more literal escape routes, and find a delicate balance between fear and education for residents and their families.

“My job is to give people control over that fear as best I can,” O’Reilly says.

Most residents have signed up for a mobile phone notification service. Signs along the highway guide travellers to higher ground and the main beaches have sirens, with plans for more in town and the nearby First Nations communities.

Tofino wants to build a vertical evacuation tower – a wave-proof structure that could accommodate thousands of people fleeing to higher ground. Similar towers have saved thousands of lives in Japan and Canada’s first tower is under construction in Haida Gwaii, an archipelago just north of Vancouver island. But the best sites for such a tower are also the most unstable, prone to liquefaction – a phenomenon that sees sandy areas mimic liquid during an earthquake.

Against all that, O’Reilly’s larger task is to grapple with the profound uncertainty of the unknown. The highways will probably buckle and crumple in an earthquake. But how many trees will litter what remains of the road, and how might that change the way people move when they are panicking in search of an escape route?

Before it was an eco-tourism hub for affluent visitors, Tofino was an outpost for the fishing and logging industries – nicknamed Tuff City. The underlying ethos, say residents, is a hardiness and a resilience to thrive against the harsh geography. Residents are accustomed to power cuts and a patchy mobile service. Implicit in the town’s disaster plans is a recognition that success in the face of disaster requires a belief in human nature.

“What will get us through a large disaster is a sense of community,” says O’Reilly. “People coming together when they’re needed is a lovely piece of humanity that emerges from unfortunate moments in the world. And we know this town will come together. Because it has to.”

For a disaster that looms as a distant threat, it occupies a similarly abstract space in the town’s culture. O’Reilly organises a “high-ground hike” event for families to learn the town’s topography. Next to the house where Goss lives, tourists snap pictures of a sign warning that the area is within the tsunami flood zone. Shops have souvenir shirts for sale with a modified design: a surfer running towards the massive wave.

“We know that it exists, but people don’t talk about it,” says Goss. “We’re not living our days in fear of a tsunami. But maybe we should think about it more than we used to.”

1 month ago

45

1 month ago

45