In a three-storey building in a residential neighbourhood in Gran Canaria, about an hour’s drive from the airport, more than a dozen teenage Senegalese boys in colourful, flowing robes sit in a circle, soulfully chanting supplications. Behind them, girls sit with their heads covered, praying. On the top-floor terrace a feast of steaming rice, meat and vegetable gravy is being prepared.

It is a bright Sunday afternoon in February. The young people are mostly asylum seekers from Senegal, who live in detention centres where conditions can be brutal, according to Spanish human rights groups.

Senegalese made up a significant proportion of the record number of migrant arrivals to the Canary Islands last year. Nearly 47,000 people reached the Spanish archipelago in 2024 via the increasingly deadly Atlantic migration route from Africa.

More of the country’s young people are leaving the west African country because of a dearth of jobs. Most want to make more money in Europe, but asylum systems abroad, particularly in the Canaries, are overwhelmed.

In this house, though, the teenagers see themselves simply as talibés, students who are disciples of the Mouride – a Sufi order with roots in Senegal. “We feel like we’re back in Senegal when we come here,” says Mame Diarra, 18, who arrived on the Spanish island a year ago and lives at a women-only holding centre.

Senegal’s Mourides make up about 40% of the country’s Muslim-majority population and are the second largest of a handful of rival brotherhoods, which date back to the 17th century, when locals turned to sects in numbers to organise against French colonisation.

Amadou Bamba, the revered founder of the Mouride brotherhood, preached non-violent resistance against colonisation and was forced into exile first to Gabon, then Mauritania. Each year, four million people mark Bamba’s exile in a Grand Magal, or pilgrimage, to the Senegalese city of Touba, the sect’s headquarters.

Mouride circles, or dahiras, like the one in Gran Canaria, are partly a school and partly a social network, connecting people of shared allegiances in a tightly knit, familial bond. That makes the group, which counts two former presidents as members, politically influential.

Bamba gained a saint-like reverence upon his return from exile, which means Mourides see migrating as sacred, says Cheikh Babou, a history professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Many Senegalese people seek to move, to earn more and send money home, but for Mourides there is an added spiritual incentive and the assurance of a safety net wherever they go.

Dahiras from Paris to New York have garnered thousands of followers who send huge amounts of money back to Touba each year for the upkeep of the Grand Mosque, one of the largest in Africa.

Their economic power means they are increasingly shaping the movement, a prickly topic for sheikhs in Touba who fear their power is being chipped away, Babou says. One dahira in Italy established a three-day marathon supplication festival, now celebrated by others, even in Senegal. Another in mainland Spain built a massive Touba hospital.

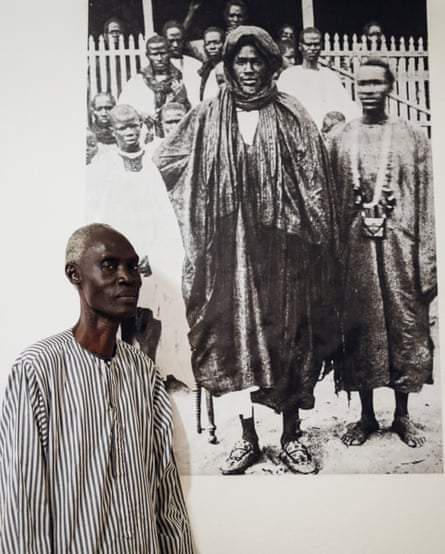

Connecting both worlds are marabouts – religious teachers who periodically visit dahiras abroad, offering spiritual advice and receiving donations. In the Gran Canaria dahira, that job falls to Abdou Fall.

The tall and thin leader takes pride in being a descendant of Ibra Fall, one of Bamba’s most beloved devotees. When he visits in February, he eagerly points out his great-grandfather’s lifesize photo in the waiting room.

In a separate, dimly lit room in the building, Papa Gueye, the island’s Mouride president, sips coffee. Members of the sect donate enough to maintain the building and the work within – even the young asylum seekers, who sometimes get a token sum from their centres, he says.

The dahira uses the money to provide food and temporary shelter to those in need; the rest goes back to Touba. Last year, the group contributed €25,000 (£21,000) of the €150,000 total sent back from Spain.

Gueye, who left his teaching job in Senegal and now works as a taxi driver, says the community is doubly needed in the Canary Islands because of the thousands of Senegalese desperately seeking residence papers or jobs after their harrowing journey from the African mainland.

Besides the problem of overwhelmed asylum centres, children fear turning 18 – when as adults they will no longer be entitled to government support. Gueye says he tries to give them “peace of mind”.

“We speak to them about their concerns and tell them to be patient [with their residence papers],” he says. “We are like their support centre.”

Around the corner from the dahira, three male talibés sit on a park bench, glued to their phones. The teenagers, all asylum seekers, are around the dreaded 18 mark.

They gather here weekly with others to pray and eat, says one of the boys, momentarily looking up from his phone and sliding off his headphones.

“It makes me feel calm, and I forget my worries,” the talibé, who came by boat a year ago and recently turned 18, says of their weekly gatherings. “I have no residence papers, making it hard to get jobs. This really worries me.”

Loueila Sid Ahmed Ndiaye, a Canary Islands-based migration lawyer, is critical of the asylum process in Spain. Unaccompanied minors under 18 are guaranteed aid in the form of emergency services, shelter and a swift review of their asylum cases. However, those rights do not automatically apply once they turn 18.

“At the age of 18, Spanish authorities say asylum seekers no longer need any form of guardianship since they are considered adults and are abandoned by the government and are left to fend for themselves,” Ndiaye says.

The Spanish government was approached for comment.

Several humanitarian organisations on the island have opened their doors to help the 18-year-olds, but housing in these reception centres is limited, says Ndiaye.

At the dahira, the soulful recital continues late into the evening, resonating peace and calm throughout the room. Soon, the talibés will have to pack up and head back to their detention centres. It will be a week before they gather here again as a group, but the dahira’s doors are always open, Gueye says.

“I just tell them that they should be more strong,” Gueye says. “Here, there’s reassurance for them.”

5 hours ago

5

5 hours ago

5