To break into the world’s most-visited museum in broad daylight, grab eight pieces of priceless Napoleonic jewellery and vanish into the Paris traffic on humble scooters may seem like the most audacious of crimes, carried out for international notoriety and ensuing Hollywood film treatments.

Experts who observe trends in international art crime, however, see Sunday morning’s heist at the Louvre as something more prosaic: the latest in a series of smash-and-grab thefts focused more on the material value of precious stones or metals than the artifacts’ significance, continuing a pattern that has emerged over the last decade in Germany, Britain and the US. The location, they suggest, would have been of secondary concern to the criminals.

“You may ask why thieves who want to steal expensive jewellery are breaking into a world-famous museum rather than a Cartier store,” said Christopher A Marinello, a leading expert in the recovery of stolen works of art. “The answer is simple: it’s because these days a Cartier store is better protected.”

A spate of violent jewellery shop thefts mean that many outlets have beefed up their security in recent years, with armed guards on their premises and wares no longer kept on display overnight. Museums, meanwhile, look more exposed, partly because of the in-built reason of being public-facing institutions in historic buildings, and partly the current economic climate in many western countries.

“Since Covid, governments across the globe have cut back on law enforcement and the culture sector,” said Marinello. “If thieves can get into the Louvre, it shows how vulnerable our institutions have become. This is a horrible time to be a museum.”

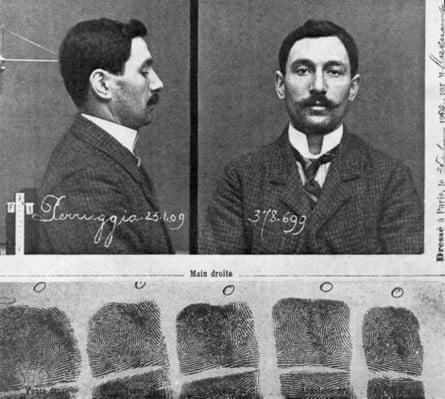

The theft of the objects – including necklaces made up of eight sapphires and 631 diamonds, the tiara of Empress Eugénie featuring nearly 2,000 diamonds and a hugely valuable crown once owned by Napoleon III’s wife that the thieves dropped by the roadside on their way out – has inevitably drawn comparisons with the 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa from the same museum, carried out by the Italian handyman Vincenzo Peruggia.

Better points of reference may be the 2019 burglary of jewellery from Dresden’s Green Vault Museum worth over €113m, the theft of a £4.75m gold toilet from Blenheim Palace the same year, the 2017 heist of a large gold coin from Berlin’s Bode Museum or even a spate of thefts of sports memorabilia from US mining museums.

In each case, the crimes appeared mostly motivated by the material value of the objects that disappeared. “There’s a simple pattern here,” said Marinello. “Smash, grab, and melt it down as quickly as possible.”

If the artefacts were to remain intact, experts say, the thieves would struggle to find a buyer. “There’s no way to sell something as immediately identifiable as the Louvre’s jewels on the licit market”, said Lynda Albertson of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art, an organisation that tracks trends in museums, including thefts and vandalism.

“They would be immediately recognised, especially given the Ministry of Culture has released images of the pieces. Even a private collector or an auction house like Sotheby’s or Christie’s would want to see paperwork establishing proper ownership before touching such striking pieces.”

In the past, museums were often reluctant to go public about the disappearance of well-known works of art and would stay silent out of embarrassment. These days, as art thefts are more widely publicised, the storage and sale of stolen art is risky business for any criminal.

“If you steal a Picasso, it has to remain intact or it becomes worthless, and you have to conceive of a scheme to keep it in hiding, perhaps by passing it around difficult criminal actors,” said Marinello. “And you’re constantly exposed to the risk of an accomplice telling the police to cash in a ransom.”

For similar reasons, the art detective Arthur Brand said it was vanishingly unlikely that the theft had been ordered, as Dutch media have reported could be the case for golden Dacian treasures stolen in January from the Drents Museum in the Netherlands. “Stolen to order is something from the Hollywood movies,” he said. “Nobody would touch this. It’s all around the world and in all the newspapers. If you buy this, if you get caught, you end up in prison. You cannot show it to your friends, you cannot leave it to your children.”

Altering stolen works by melting down or re-cutting does reduce the value. When it comes to diamonds, it also comes with considerable risk because contemporary cutting techniques give stones a larger and lighter surface area, and antique-cut stones would either draw unwanted attention or barter the price down for a coverup.

after newsletter promotion

Crucially, however, melting down or re-cutting eliminates the evidence of the crime. “My guess is that the Louvre thieves will try to take the stolen goods to places with diamond expertise like Israel, India or even as close as Antwerp, and find someone to cut out the gems,” said Marinello.

The heist at the Louvre has already raised questions about security measures at the museum, with a leaked state auditor report expected to be published next month criticising “considerable” and “persistent” delays in updating equipment and noting that security cameras were lacking in many rooms. But security experts say displaying precious items in historic buildings with a steady stream of visitors comes with risks that are impossible to eliminate completely.

“Historic buildings are much harder to protect,” said Erin Thompson, a professor of art crime at City University of New York. “Many of them have nice big street-facing windows that makes it easy for thieves to get away, and there may be building protection statutes in place that mean you can’t fit them with proper bulletproof glass.”

The most solid security systems for buildings should be conceptualised “like a fortress”, said Peter Stürmann of the German security company VZM, which advises museums and archives. “There should be several layers to repel attackers.”

Modern buildings are fitted with state-of-the-art external CCTV cameras or in-built seismic detectors that raise alarm about a smashed window in real time, but old museums may be reluctant to uglify their exteriors. Laser scanners can be hard to fit to stuccoed ceilings. Motion and sound detectors may also have to be disabled during the day as hordes of visitors stomp through a museum.

The timing of the Louvre raid, which took place between 9.30am and 9.40am local time, was typical of recent thefts, Stürmann said. “There’s a good reason why thefts tend to happen at either opening or closing times. It’s often when guards change their shifts and before the museum is full of visitors who effectively act as additional security staff.”

Technological progress may have thrown up new gadgets that can raise the alarm more quickly and efficiently, but it has also given thieves new tools with which to circumvent security measures. In Paris, the robbers reached the museum’s first-floor window with a vehicle-mounted ladder and cut through a glass panewith a battery-powered disc cutter.

Elaine Sciolino, the author of Adventures in the Louvre: How to Fall in Love with the World’s Greatest Museum, said the conversation in France about the 232-year-old building had mostly focused on crowd control in recent years, and less on security.

The museum has an on-site brigade of about 50 permanent firefighters, or sapeurs-pompiers, but their mission is mainly to protect the collection from fires and flooding. “There is no rapid-response unit,” Sciolino said. “Ultimately, the security of the Louvre all comes down to political will and money, and currently France simply has no money.”

Additional reporting by Senay Boztas

2 months ago

53

2 months ago

53