A couple of years ago, I began investigating non-fatal overdoses.

Coverage of the US’s opioid crisis has largely focused on lives lost. But through my cousin Mason, I saw another toll of the epidemic: the people who survive overdoses but are left with devastating disabilities.

Watching his and his parents’ struggles – and knowing he was not the only young overdose survivor in a nursing home – I wondered: how many people like Mason were out there? What happens to them, and how do their families cope?

I quickly learned that no one is tracking these cases. There is no official count of people living with overdose-related brain injuries. But through Facebook groups and GoFundMe pages, I began to connect with families going through similar ordeals.

Despite the pain and relentless demands of their situations, many were open and generous with their time. That was especially true of Jessica Pittizola Jarrett and her son, John-Bryan, who goes by JB and suffered an anoxic brain injury and other complications after overdosing on fentanyl in September 2020. Between managing JB’s 24-hour care, her own workload, and helping other families navigate similar crises, Jessica still made time to speak with me.

Last December, she and JB welcomed me into their home in Sugar Land, Texas, where they live with Jessica’s brother. Nothing about their lives struck me as easy – from operating the Hoyer lift to get JB out of bed, to loading up the van for medical appointments and family outings. But being with them in person only deepened my admiration for their strength, five years into their new chapter.

I already knew of Jessica’s fierce faith and commitment to JB’s recovery, but what stood out most was the spirit she brings to caring for her son: organizing a tattoo fundraiser in his honor, tracking down a wheelchair in his favorite color (hot pink), finding small ways to inject joy into the daily grind. Love, as much as endurance, sustains them.

Nurse Kenneth Emakpose, uses a Hoyer lift to help JB out of bed in the morning. Luckily, JB did not get added to the US’s tally of overdose deaths – an estimated 81,000 in 2023 – and more than 1m over the past 20 years. The tragedy of his overdose is that having survived, the 29-year-old now lives with profoundly debilitating, life-changing injuries. Nearly five years on, JB cannot walk or talk. After some recent medical setbacks, he also struggles to move, to swallow or to communicate in any way.

Emakpose brushes JB’s teeth during his morning hygiene routine.

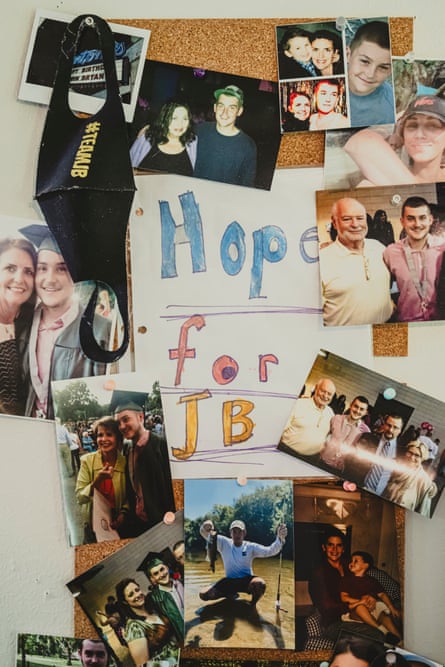

Family photographs hang on the wall of JB, before he sustained an anoxic brain injury in 2020, during a fentanyl overdose.

Jessica drives her son to a medical appointment in the family’s handicap-accessible van.

Jessica wipes sweat from JB’s face, trying to keep him comfortable as she and medical staff at the Texas Institute of Rehabilitation and Recovery, better known as TIRR-Memorial Hermann, troubleshoot a non-functioning wheelchair ramp on her van.

Jessica celebrates finding a physical therapist with a portable wheelchair ramp, to help get her son out of her handicap-accessible van – after their electric ramp stopped working outside a medical appointment.

Jessica wheels her son to attend a medical appointment at TIRR-Memorial Hermann, one of the nation’s premier brain rehabilitation centers. The Houston-based hospital has a reputation among the anoxic brain injury community for accepting patients with the most severe injuries and treating them as people with futures and potential.

Jarrett stresses about a broken wheelchair ramp on their family’s van, while at a medical appointment with her son.

Nurse Ngozi Uketui prepares to refill JB’s intrathecal Baclofen pump – a surgically implanted medical device that delivers muscle relaxers directly into his spinal fluid.

Jessica comforts JB, while Uketui refills his intrathecal Baclofen pump.

Dr Cindy Ivanhoe, a professor of physical medicine at UTHealth Houston and director of the spasticity program and associated syndromes of movement at TIRR-Memorial Hermann, consults Jessica and JB.

“It’s a very hard system to navigate. It’s very hard to advocate.” “Some patients get better, some patients get worse,” says Ivanhoe. “We are not great at predicting who’s going to do what, and so I would just not like to take those opportunities away.”

But that’s what insurance companies often do, she noted, adding that exasperating phone calls with medical directors over coverage of rehabilitation or other treatments are a routine part of her job. “We teach people to practice based on what the insurance covers, not based on what’s possible,” says Ivanhoe, who has treated thousands of patients over her decades-long career.

Jessica wheels JB from a medical appointment at TIRR-Memorial Hermann.

Brittney Burton, an occupational therapist, works with JB on the motor planning necessary for communication using a head laser and low-tech communication board, in preparation for use of an augmented communication device in the future.

JB answered “yes” when she asked if he was tired, then pointed the red laser beam to “no” when she asked him if he wanted to go to bed.

Burton, uses a Stimpod NMS460 – a neuromodulation device, on JB’s face, to stimulate his nerves to promote neurotransmitter activation and sensory stimulation.

Brittney Burton and Jessica stretch JB’s tightly clenched hands.

JB relaxes in a recliner and watches a baseball game.

Jessica prepares her son for sleep for the night.

JB sleeps under a starry sky nightlight in his bedroom. For peace of mind his mom now sleeps in his bedroom closet, her makeshift bed wedged between the wall and a rack of clothes – close enough to respond to every cry, call, shift of bedsheet, or other sign that JB is in distress.

Jessica embraces her son at night.

-

Meridith Kohut is a photojournalist based in Houston, Texas, who has documented health, humanitarian and environmental issues in the US and Latin America since 2007

2 months ago

60

2 months ago

60