In 2000, my dad wrote me a letter saying he found it hard to love me. “I don’t even understand you,” he said. He slipped it under my bedroom door when I was at my lowest point. The sentences split me wide open.

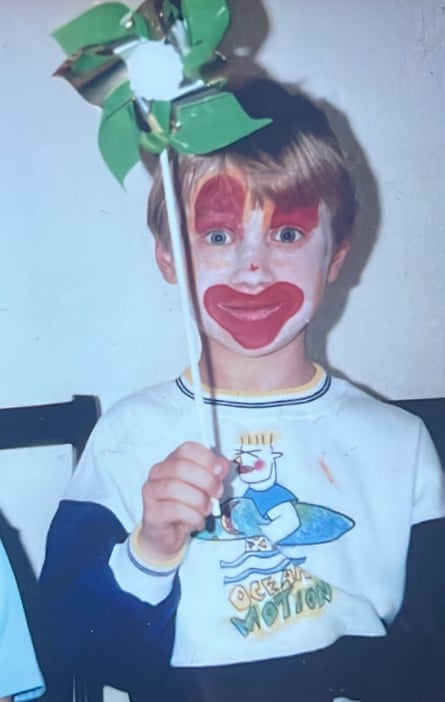

I was always the pretty little boy in the corner of the playground, plaiting girls’ hair, dreaming of spotlights. My flamboyance didn’t seem to have an off switch. Dad tried his best to steer me into his version of a “proper” boyhood: football boots, muddy knees, the whole shebang. He’d tap my limp wrists into place and drag me to self-defence lessons in an attempt to turn them into karate chops.

Maybe I embarrassed him – I wasn’t just different, I was loudly different. Maybe he saw me as a reflection of himself – if his son was soft, then what did that make him? Maybe it worried him, too – it’s a dangerous world out there, and his paternal job to protect might have felt compromised.

When I was 15, London became like sticky flypaper to me. I’d get the train from Kent, fake ID in my pocket, to wallow in a fug of sweat, smoke and pulsing bass. I began to live a double life, blissfully shielded from what society – and my father – expected me to be. I found booze and party drugs, and tethered myself to a motley crew of older friends. I was on an adventure.

Weekdays in suburbia moved in polite, predictable slow motion. School slouched by. Then, on Saturday nights, everything shifted into light speed. Nightclubs felt fast, dizzying, alive – and I got lost in their pace.

It all came crashing down, of course. My growing truancy sparked suspicion, and my school outed me – not explicitly, but with concerned calls home, a comment about “behaviour” or “peer dynamics”. I was dragged out of the closet – and off the dancefloor – in one brutal swoop.

I remember a Friday evening, after school, being called into the living room for “a talk” with my dad. I was so nervous I could taste my own heartbeat, my guts twisting into knots.

“Are you queer?” he asked – blunt, no frills. I replied, defiantly, “yes”, then turned to hide my trembling lip. I told him I was proud to be who I was and had no plans to change. He slid the letter in question under my door that night.

From then on, a silence settled between us. He couldn’t even face eating dinner in the same room as me and I found myself slipping into a profound and non-negotiable depression.

We looked alike – identical, in fact, when I saw pictures of him at my age – but in that moment it became my mission to reject every one of his character traits. At 18, I moved to London, the city that promised reinvention. There, I could be someone else entirely.

I learned early to mask, to put my guard up. Drag became my canvas. I worked in nightclubs, and suddenly I was getting attention from adoring crowds, but only by disguising myself. I was caught somewhere between a fierce desire to be seen and the reluctance to be truly known.

Behind the DJ decks, I earned respect for my creativity – something my dad once nurtured, even if he couldn’t have seen where it would take me. My partying multiplied – nights so wild they often left teeth marks.

Many of my new friends shared similar stories: disappointment from their dads lurking beneath the glitter.

Distance helped. Despite our differences, we strained a relationship, going through the motions for a few more years. But I kept my Jodie persona a secret – he already struggled to look me in the eye.

One day, his wife called me. They’d been watching a TV makeover show, she said, and I’d popped up in a guest spot I’d filmed. I was in full drag regalia, but my dad recognised my voice, and my second coming out took place. There was no confrontation; he simply stopped communicating with me for ever.

This time, it wasn’t shocking; it felt almost procedural. But it hurt even more. I was rejected for my creative expression, the thing most dear to me. The parts of me that were deemed interesting to others were the parts of me that scared him.

After a decade and a half, I’d stopped wondering if a birthday card was going to land on my doormat. I became grateful for his absence. The loss became the furnace that forged me – fuel for my unyielding drive to prove I could, and would, make something of myself. Dad’s abandonment left a vacuum, and in that space, I built a career.

“Should I write him my own letter?” I once asked my sister. “Don’t bother,” she said, flatly. “You won’t hear back.” I realised we were going to remain in this cold war until one of us died.

And then, he did.

Dad had a heart attack last year. It was too late to reconcile. No dramatic deathbed reunion, no final phone call, just a quiet conclusion.

I’m glad I went to his funeral. I hid towards the back, realising almost no one there knew he had a son.

My bitterness lifted, and I realised some relationships don’t need to be forced into repair. Not every party ends with hugs – sometimes the lights come up and the music just stops.

-

You Had To Be There by Jodie Harsh is published on 25 September by Faber (£20). To support the Guardian order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

3 months ago

54

3 months ago

54