Over four years have passed since the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan. Claudia Janke’s photographic series features 7 Afghan women who have found safety in the UK after escaping at great personal risk. She worked using an Instant Box Camera, the only type of camera allowed under the Taliban’s first regime, reclaimed for the these women to amplify their voices

Since the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in 2021, the regime has imposed sweeping restrictions on the rights of women and girls, with devastating consequences for society. Girls are barred from attending school beyond the sixth grade, and women are prohibited from working, appearing on television, leaving the house alone, and singing or speaking in public. They have been systematically erased from public life.

A recent UN Women report underscores the scale of this repression. The Afghanistan Gender Index 2025 reveals, among other findings:

-

No female representation in national or local decision-making bodies.

-

A complete ban on secondary education for girls.

-

A staggering 76% gender gap across health, education, finance, and governance – one of the worst in the world.

Despite this, political voices in the UK frequently call for deportations to Afghanistan. And the voices of those most directly affected are largely absent: female Afghan refugees.

The Instant Box Camera, also known as the Afghan box camera, was the only type allowed under the first Taliban regime (1996-2001) and was primarily used for taking passport photos of men. Reclaiming the camera for this project highlights the power of visibility and storytelling. The aim of the series is not only to show the faces of these women but to amplify their voices.

Maryam Khurram, urban designer, London

I am an architect and artist from Kabul. I was born during a time much like now, when girls were banned from education.

My mother refused to accept this. She home-schooled me and my sisters, teaching us everything she could. Thanks to her courage, I received an education many Afghan girls were denied.

My family’s life is very limited. My sister’s biggest joy now is sitting in the back seat of the car while my brother shops. She wears a mask, stays hidden, and watches the city go by. That’s her only escape from the house. I often feel guilty walking freely around London.

I work as an assistant design manager on the HS2 rail project and volunteer with the IRC to help Afghan refugees in the UK.

I’m grateful for every opportunity here, but my dream is to return home one day. No nation can thrive by silencing half its people. I want to return to Afghanistan with knowledge, experience, and the strength to help rebuild my country and restore hope.

Sharareh Sarwari, TV presenter, London

From birth I had no rights simply because I was born female. Women in my village weren’t allowed to go to school or even leave the house.

I was born in 2003 outside Herat, just after the first Taliban regime ended. Fortunately, my parents believed in education and pushed me and my sisters to study.

When I turned 18, the Taliban returned. Because of my activism, my family went into hiding, avoiding anyone who might expose me. Eventually, the Taliban found me in Kabul. They detained and questioned me for three days, before releasing me with a warning to stop what I was doing.

When I returned to Herat, everything had changed. Men wore traditional clothes, women covered their faces. Shocked by my arrest, my family feared for my safety. But I couldn’t stay silent. Alongside a small group of women, I organised protests in secret and spoke to international media.

We marched in the streets until soldiers came, then ran in all directions. One of us was dragged into a vehicle.

We don’t know if she came back.

In the UK, I finally feel safe but fear never fully leaves me. I can live freely, yet I carry the trauma of life under the Taliban.

I work as a sports presenter at Afghanistan International Television, sharing stories that matter to my community. I’ve recently started studying journalism at university. My dream is to one day work with the BBC, Sky or the Guardian but above all, to bring my family safely here so we can live together.

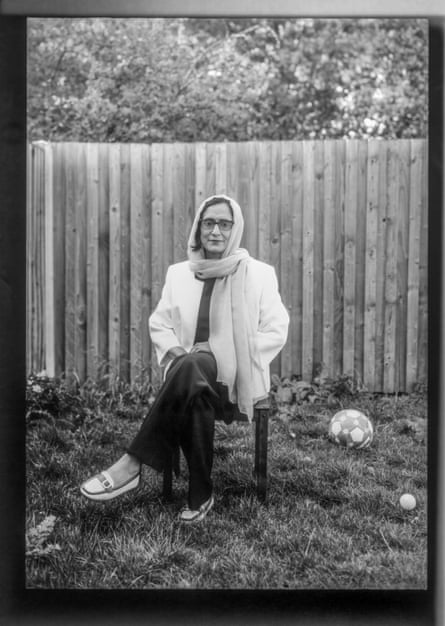

Bahaar Joya, ICU nurse and journalist, London

My life began in exile. From the age of five to 14 I lived in Abu Dhabi, far from Afghanistan. My father was a general in the former president Mohammad Najibullah’s army and fled the country after the war with the Mujahideen.

After the fall of the Taliban my parents decided to return home. They were full of hope, ready to help rebuild our country. Kabul was in ruins, dusty and scarred by decades of war. My father joined the new army and my mother returned to teaching. Afghan society was deeply traditional and religious. I was constantly criticised for my clothes, for my opinions and simply for existing. I loved playing football but was told girls shouldn’t play because it could “destroy their virginity” – hearing this sparked a rebellion in me.

I began questioning everything: the meaning of “honour” and why women’s lives were defined by shame and control. With a few friends, I formed the first girls’ football team at my school. We faced resistance from teachers and relatives, but we played anyway. It was my first victory against social taboos.

I entered university to study sharia law, but discovered a passion for storytelling and joined Radio Sahar, a women-run station in Herat. I started by making tea and cleaning desks, studying discarded scripts to learn the craft. Eventually I was given my first report on gender discrimination at the university, where female students were banned from the cafeteria to prevent “evil thoughts”. The piece launched my career as a journalist. I was 17.

Soon after, I created a TV programme called The Lost Place for Women, asking: “Where do women belong in this society?” The first episode focused on women who burned themselves to escape domestic violence because divorce was forbidden.

It caused outrage and was temporarily banned but it ignited a national conversation.

In 2010, I won a scholarship to study political science in India. My father tried to stop me, fearing for my reputation, so I forged his signature on my passport.

India changed my life. It was my first experience of freedom and life without fear. When I returned to Afghanistan, I joined the BBC’s Persian service and became the first Afghan woman to appear on camera in Kabul without a headscarf. I dyed my hair blond and refused to cover it. I was confident and unapologetically myself. That act alone made me a target.

In 2015, I witnessed the brutal lynching of Farkhunda, a young woman falsely accused of burning the Qur’an. I tried to reach her, to stop the mob, but she was beaten to death. The next day, I joined other women to carry her coffin, defying religious custom. Her death changed me for ever.

Not long after, I was attacked and stabbed in Kabul for my work. The police told me to drop the case “for my safety” and released my attacker. With the BBC’s support, I fled Afghanistan and sought asylum in the UK in 2016.

I was haunted by what I had experienced and struggled with PTSD and depression. Years of therapy helped me heal.

Today, I work as an ICU nurse and a freelance journalist. I still tell women’s stories and produce health programmes for BBC Persian reaching Afghan women, who have lost access to care.

My mother is still in Afghanistan and runs an underground school for girls teaching maths, science and history. She has been arrested many times but refuses to stop as these girls are our future.

Her courage reminds me that Afghan women are unbreakable. I may be far from home, but my fight continues through journalism, my work as a nurse and the belief that women deserve dignity and the right to choose their own lives.

Fatemah Habib, project manager, London

I lived in Afghanistan until 2021. I was raised in a small, educated family – my mum, two sisters, one brother and me. My father was killed when I was six years old during the first Taliban regime. My memory of that time is fragmented because I was very young, but I do remember his death. Men came, took him away and returned his body covered in blood and injuries. We never found out who killed him.

I remember new faces in the streets and that one day I wasn’t allowed to go to school any more. I remember my mum’s tireless efforts to make ends meet as a widow in a country where she had no rights.

She risked everything to keep us learning, giving secret classes in our basement to us and local children.

After the first regime fell in 2001, my secret education enabled me to later earn a bachelor’s degree, a leadership diploma, and a master’s in Kabul. I spent 15–16 years working with UN agencies, embassies, and women’s advocacy groups. I worked with the British embassy, British Council and the National Democratic Institute. It was an inspiring time, I never imagined I would have to leave. But because of my work for British institutions, I was eligible for evacuation and arrived in the UK in 2021, days before Afghanistan collapsed.

Life in the UK was difficult at first and was a real culture shock. For seven months we lived in a hotel with limited access to services, my husband and I trying to work and care for our small children all in one room. But over time we settled. I finished my business administration master’s and no wam working with the British Council again. We live in London and life is much calmer, though we face challenges around high costs of living and missing family and home. My mum and siblings have recently been evacuated to Australia, which is a great relief.

When the Taliban returned in 2021, we hoped this time might be different but what followed was devastating. Women who once led schools, hospitals, and organisations are now confined to their homes. They cannot participate in society or move freely without a male escort.

From my perspective, the regime does not accept women as human beings.

The economic impact is huge: families are starving, poverty is increasing. Girls are being pushed into early marriage. My friends say: “We are living, but we are not alive.” What the world sees in the media is only a fraction of the soul crushing reality.

I wish the international community would stop the endless conferences and speeches and take real action. This is an emergency, yet Afghan women have been abandoned.

My greatest wish is to return to a free and peaceful Afghanistan, to walk on its soil, breathe its air, and stand with Afghan women again. I’ve told my husband that if I die, I want my body returned home, because my heart will always belong there.

Aqlima Amiri, lecturer, London

No regime can stop me from learning or achieving. Education is my revenge against oppression.

I want to show that even from exile, I can reach the world’s top universities.

I grew up in Kabul. My parents encouraged me to study from the very beginning. They made sure I was attending a secret school from a very young age during the Taliban’s first regime. I must have been under six.

Before I started school, my father had already taught me to read and do arithmetic. He used to visit my school to encourage me and my classmates to study hard.

My mother never had the chance to go to school, but is one of the wisest women I know. When I stayed up late studying, she would bring me food or tea. Her strength and love held everything together.

After school, I studied biology at Kabul University. I graduated with distinction and soon after was hired as a lecturer of cell biology and general botany. Doing this at such a young age felt like an honour. I saw it as a way to serve my country.

In 2019 I received a World Bank scholarship to pursue a master’s degree in Malaysia. I was finishing my studies when the Taliban returned to power in 2021. Everything changed overnight.

I decided not to return home. The uncertainty and financial stress of this time were extremely difficult. The relief came when I received a Chevening scholarship and came to the UK to study environmental technology at Imperial College London.

Coming to the UK was not easy; it is a completely different world. I was fortunate to speak English but I still felt lost. I am grateful to be safe here but struggle to feel a sense of belonging.

The hardest part is starting from scratch so far from my family. Some days it feels too heavy, but I remind myself why I’m here: for my sister, for the girls who can no longer study and for all Afghan women.

If I could send one message to the women of Afghanistan, it would be: don’t give up. I know the pain, fear, loneliness and injustice but I believe the only way out of darkness is through education, courage, and persistence. Even the longest night will end and light will return.

And to people around the world, I would say: we are all human beings. Our voices and actions matter. Together we can work towards a fairer world, where every person has the right to learn, to work and to live with dignity.

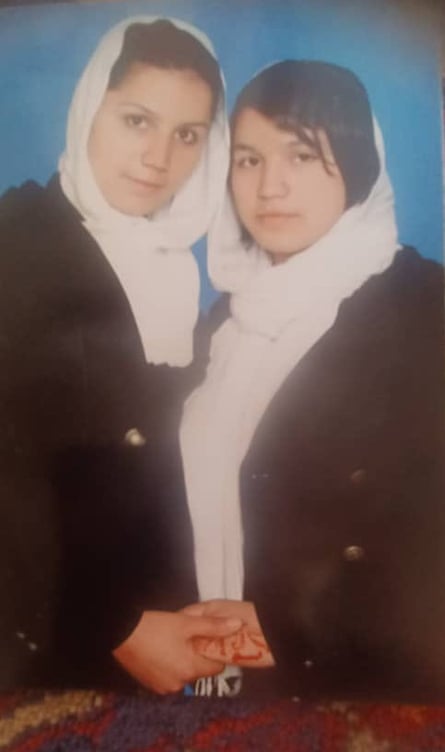

Najiba Hadaf, journalist, Barnsley (Surname changed)

I will never understand why the international community handed Afghanistan back to the Taliban after 20 years. Their withdrawal felt like a betrayal. The Doha agreements were full of promises, but they left us with nothing and we have to endure the consequences. When the Taliban collapsed in 2001, we were relieved. Girls went to school again, women went to work, and people began to rebuild their lives. But now, everything has collapsed again.

For women and girls, it is always the hardest.

I was at work in Kabul when everything changed in 2021. President Ghani had fled the country and panic spread. But I felt calm. I couldn’t believe the international community would truly abandon us. That night, it became clear this was a total Taliban takeover. From then on, I stayed at home, too afraid to go out.

I am a journalist. I worked for Bakhtar news agency, Voice of Afghan Women Radio and for government publications. In 2002, I interviewed Jack Straw, then Britain’s foreign secretary, when he visited Afghanistan. He invited me and a group of journalists to the UK to learn about the profession. It was a great experience.

Under the Taliban, women can no longer work in journalism, and independent media has almost disappeared.

Afghanistan has only known war. When the Taliban first appeared in the 1990s, people hoped they might bring peace. They seemed different. They initially allowed women to work, but within a few years, that ended. When they returned in 2021, we knew what to expect.

As a female journalist, I was in constant danger. I applied for resettlement through the UK government with my husband and two younger children but we had to leave behind the rest of the family. Life here is safe. My children go to school and I study English.

But I have lost everything: my job, my loved ones, my country. I worry constantly for family and friends still in Afghanistan.

My sisters call me every day with news. People are hungry, sick and without hope. Recently Pakistan has attacked Afghanistan and people I know have been killed.

I don’t understand politicians who say Afghanistan is “safe” and that refugees should return. It is not safe. People flee because survival is impossible. If there were safety, work and freedom, I would never have left.

I worry about young Afghans who come here. Many are seeing freedom for the first time and struggle to understand new laws and cultures. They need guidance, not punishment. Deporting them is not the answer.

I’m asking the international community: do not forget Afghanistan, and do not forget Afghan women and girls. For 20 years, we had hope. Now it has been taken away. Afghanistan needs leaders who care about the people and real global cooperation to rebuild the nation.

My story is just one among millions. Every woman in Afghanistan carries her own story of loss and pain but also resilience.

Nilab Mohammad, interpreter, Barnsley

Women in Afghanistan are like birds with clipped wings: they are not allowed to fly.

I have lived in the UK for 12 years with my husband and our three children, but most of my family still live near Herat in Afghanistan. In 2021, I was at a picnic when my phone wouldn’t stop ringing. Friends and relatives were crying: “The Taliban are back. We don’t know what will happen next.” I cried too, it felt like the end of the world.

I was a child during their first rule. I still remember how the Taliban took my father away and jailed him, simply because he was from Panjshir Province, which resisted them. My mother is an incredible woman, she kept us alive by sewing burqas for a local shop. We had no electricity, so she built a small power system using a bicycle. My brother and I woke up at three in the morning to pedal and power her sewing machine. Sometimes we were so hungry we ate leaves meant for animals. That is how we survived until my father was released and we escaped to Pakistan.

After the Taliban fell in 2001, we returned home full of hope. But since their return, all this ended.

My family has suffered. One of my brothers was killed in a suicide attack, and the other died from an electric shock while fixing a socket. When I went to his funeral in 2022 I could feel how much the country had changed. The streets were near empty, similar to a Covid lockdown.

My mother, who studied law and worked all her life, is now trapped at home and depressed.

My sister, who graduated in engineering on the very day the Taliban returned, was forced to study midwifery instead. Now even that is forbidden. She told me: “We are like bodies without souls. We breathe, but we are not alive.”

Three years ago, the Taliban threatened to seize girls from Panjshir families for forced marriage. At only 15, my younger sister married quickly out of fear. My other sister refuses altogether. She says she would rather die than be forced to marry a Talib or any Afghan man.

In Afghanistan, women have no protection or choice. Here in England, there are laws and rights, and justice. Many Afghan women I know here have left abusive husbands because they understand they are free.

I came to the UK at 18 to join my husband. I studied hairdressing and earned a diploma, though my dream as a girl was to become a pilot or an astronaut. That dream feels impossible for me now but my daughter, Sarah, wants to be an astronaut. Maybe she will fly for me.

I volunteer with the Refugee Council helping newly arrived Afghan women find friendship and confidence. I know what depression feels like, and I don’t want them to suffer in silence as I once did. I organise events and gatherings to remind them they are not alone.

Here in the UK, I feel safe and human. In Afghanistan, I would feel like a donkey carrying heavy loads with no rest or choices. That is what life for women is like there: hard, hopeless and without freedom. But I still hold on to hope that one day, things will change and that every woman, every girl will be able to live freely and truly spread her wings.

1 month ago

57

1 month ago

57