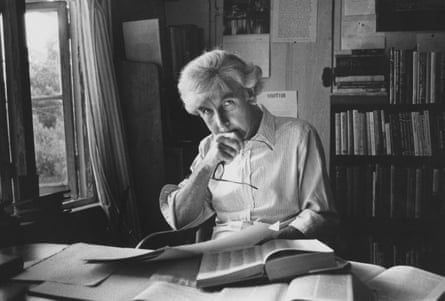

One hundred years of a unique literary rural life will be made available to readers and researchers after the British Library acquired the archive of Ronald Blythe.

The author of Akenfield, a globally bestselling account of a Suffolk village in the throes of the agricultural and social revolution at the end of the 1960s, lived and wrote in East Anglia until his death in 2023 at the age of 100.

As a former librarian who remained firmly in the pre-computer age, Blythe’s papers were found to be immaculately ordered – a million words or more, in neat writing, in humble school workbooks and on index cards.

Even so, curators estimate it will take a year to fully catalogue his archive and better understand the treasures hidden in his books, letters and cards.

“He was so orderly,” said Ian Collins, Blythe’s biographer and literary executor. “When people say ‘archive’ it’s usually another word for ‘muddle’ but with Ronnie you can tell it’s the product of an amazing, self-trained mind.”

Blythe was born in abject poverty, a Suffolk labourer’s son whose family slept on mattresses made of straw. He never went to school or university but taught himself, through reading and friendships with artistic, bohemian rural residents, particularly the artists John and Christine Nash. He published more than 40 books in his lifetime, including social history, fiction, poetry, rural nature writing and essays.

Helen Melody, the lead curator for contemporary literary and creative archives at the British Library, said: “We are delighted to have acquired Ronald Blythe’s archive, which will be a wonderful resource for Blythe scholars and those interested in the societal and cultural changes that Blythe’s work chronicled.”

According to Melody, the archive offers “an amazing insight into the century he lived through because he did a lot of reflecting backwards as well as thinking about contemporary events too”.

Blythe’s papers reveal the depths of his research for Akenfield, which tells the vivid and unvarnished story of a Suffolk village through the voices of its inhabitants, young and old. He writes to the Ministry of Agriculture to obtain records of the cows and geese kept in the village of Charsfield, his model for fictionalised Akenfield, while his index cards show he spoke to hundreds of people, seeking out everyone from otter hunters to commuters to create a kaleidoscopic and authentic account of rural life.

His notebooks show how his interviews were written up immediately afterwards, almost always from memory, according to Collins.

“He listened very, very attentively and he had this incredible memory because he’d been so watchful as a child, and he was very good at catching his interviewees’ voice,” said Collins. “All his books are true but it’s a deeper and broader truth than verbatim. That’s why Akenfield resonates because it’s not just 49 interviews from that period; it’s as though Thomas Hardy was interviewing them. Oral history tells us what people did; Ronnie tells us what people are.”

The archive reveals Blythe’s frugality, with the writer reusing index cards, and paper, and cramming as many neat words as possible into each cheap school notebook. Collins said his habits went to the heart of his “genius” as a writer, too. “It’s so neat because he knows that paper is precious, ink is precious and words are precious. Every word has to work so he’s constantly revisiting and honing it down to get the essence of it all. There’s no waste. He hates waste. You’d think that would make him into a puritan but we know from his life he wasn’t that at all – he was a hedonist.”

Blythe was a hermetic figure who lived alone on the Essex border for most of his life and held a sturdy Anglican faith but Collins’s biography revealed his sociability and uninhibited gay sex life, even in rural East Anglia in an era when homosexuality was outlawed.

This Blythe is found in the archive’s collection of letters from the American novelist Patricia Highsmith. “Ron” and “Pat” struck up an unlikely friendship and even slept with each other on one experimental occasion.

The archive includes letters from fans in the US, where Akenfield was a surprise bestseller, and the occasional critical note, such as a missive from the Earl of Stradbroke who criticised Blythe for the honesty of his depictions of the friction, exploitation and misery in neo-feudal relationships between lords, landowners and farm labourers.

“Those of us whose families have for generations cared for Suffolk are, I am sure you will understand, jealous that its good name should not be smirched,” wrote Stradbroke.

In a characteristically polite but steely reply, Blythe wrote: “Akenfield was never intended to be a public relations exercise for Suffolk but a statement about human nature in the context where I most understood it.”

Collins added: “Ronnie was endlessly kind, endlessly gentle and he’s endlessly tough.

“It’s an important archive for Britain. He was a humble person but he knew his worth and he always said his papers should go to the British Library. It’s such a rich archive, he is a writers’ writer but also the writer for every person – you can recommend Ronald Blythe to anybody.”

1 month ago

66

1 month ago

66