During the final stretch of Canada’s spring election campaign, Mark Carney told a debate audience that China was the country’s “biggest geopolitical risk”. He pointed to its attempts to meddle in elections and its recent efforts to disrupt Canada’s Arctic claims.

When Carney’s government plane touches down in Beijing this week, it will be the first time a Canadian prime minister has been welcomed in nearly a decade. The trip, undertaken amid the rupturing of global economic and political alliances, reflects a desire by Ottawa to mend a broken relationship with a global superpower that uses its vast and lucrative market to both woo and punish countries.

But Carney’s state visit, the result of methodical diplomatic calculations, also speaks to the pain of a trade war with the US and an urgent need to expand Canada’s exports in order to offset mounting economic punishment inflicted by its neighbour and largest trading partner.

“There is a risk that China views Canada as weak, struggling and abused by President Donald Trump’s administration – and it sees an opportunity to present itself as the reasonable and stable adult in the room,” says Michael Kovrig, a former diplomat and senior Asia adviser for the thinktank International Crisis Group. “The Communist party has given up persuading people that they’re benevolent. Instead, they offer competence and predictability. But it also gives Mark Carney leverage to say: if you think our relationship with the United States is getting worse, what are you willing to give us?”

Despite the diplomatic cordiality on display, those briefing Carney “don’t have any illusions about the kind of leader they’re dealing with”, says Kovrig. “This is a fraught relationship.”

Kovrig himself reflects the perils of the relationship. In 2018, Chinese officials ordered the detention of Kovrig and fellow Canadian Michael Spavor, jailing the pair for more than 1,000 days in protest against “a political frame-up” and “persecution” against the telecoms executive Meng Wanzhou. The arrests and subsequent diplomatic standoff quashed any hope of Canada negotiating a long-sought free trade agreement. For years, Ottawa has looked to China as a key market for its heavy oil, metallurgical coal, timber and agricultural products.

Carney has framed the visit to Beijing as an attempt to create a “stable” relationship with China, despite allegations of Chinese meddling in Canada’s electoral system in recent years, though none of its efforts are believed to have swayed the results of the past two elections.

China has also shown a willingness to take punitive steps against key Canadian industries. After Canada joined the US in putting a tariff on Chinese electric vehicles in 2024, Beijing placed 100% duties on Canadian canola oil and meal and months later, added an additional 75.8% anti-dumping tariff, shutting Canadian producers out of their second-largest market.

“In a normal circumstance would you do any business with someone who is involved in blackmail, hostage taking and mass human rights violations and, quite possibly, crimes against humanity?” says Kovrig. “Of course not. But China is the outlier case because it’s so large that you can’t just shun it. And you have to carve out a space for diplomacy and economic opportunities because if Canada wants to defend its sovereignty and remain a prosperous country in the world, then it needs to find ways of attracting foreign investment.”

Shifting from ‘America First’

Since becoming prime minister, Carney has signalled he wants to reset the relationship between the two countries, pushing a “reliance to resilience” plan to diversify trade away from the US which, until recently, bought 76% of Canada’s exports. But the “America First” economic policy pursued by the White House has forced Carney to rethink the foundational structure of his country’s economy.

While Canada’s federal government has looked to its new Indo-Pacific strategy to forge new partnerships, Canada also wants to grow its presence in China, which makes up only 4% of exports.

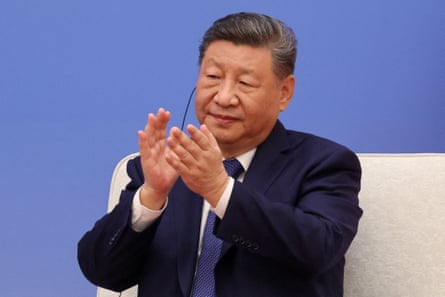

Following a string of meetings between Canadian senior ministers and their counterparts, in September, Carney met Chinese premier Li Qiang and a month later, Carney spoke to President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the global summit in South Korea, telling reporters the relationship between the two countries had reached a “turning point”.

The January state visit reflects a “very deliberate and incremental diplomatic dance” between the two parties, said Roland Paris, the director of the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa.

Paris, who also served as a foreign affairs adviser to the former prime minister Justin Trudeau, says Beijing and Ottawa have a number of overlapping interests, noting the talks are expected to centre on energy, agriculture, international security and trade between the two countries. But hopes that the meetings lead to a removal of retaliatory tariffs on Canadian industries requires careful diplomatic manoeuvring.

“The logic for [the last two Canadian governments] was that it’s possible to have trade with China while also trying to work on points of difference between the two countries,” he said. “You can walk and chew gum at the same time.”

Canada has long seen its liberal values as a core component of laws and institutions and by extension, its foreign policy – something that has frustrated Chinese officials. Among the frictions for Canada are a swath of human rights abuses by China, sustained allegations of electoral interference and Chinese actions in the Arctic.

“It’s important to remember that China is not our friend,” says Margaret McCuaig-Johnston, a senior fellow at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs. “This is not a country that follows reasoned arguments and wants to have friendly relations. The geopolitical and transnational repression risks that have long concerned Canada have not changed.”

She points to China’s decision to execute four Canadian citizens, despite protests from Canadian officials, Ottawa’s concerns about the conviction of pro-democracy activist Jimmy Lai and China’s increased presence in the Arctic, including placing monitoring buoys in waters Canada considers its own.

“It’s understandable that the prime minister is looking for other markets. We do need to diversify – that’s very clear,” McCuaig-Johnston says, adding that Chinese investment in Canada’s oil and gas industry was “safe” but worries about Beijing encroaching into the clean energy sector. Her research has profiled numerous instances of joint-ventures that end with Canadian companies leaving “out of frustration and in despair” and their Chinese counterparts keeping the Canadian intellectual property, the technology and the equipment.

“The reality is: we should stay miles and miles away from any discussion of aerospace technology, artificial intelligence and critical minerals,” she says. “This is a very challenging diplomatic trip and I hope we can make some safe deals on trade, but we must be careful about not opening up other sectors and putting them at risk.”

Analysts say a successful visit by Carney is likely to lead to a flurry of near-term agreements that serve the interests of both sides. But Kovrig hopes that behind closed doors, Carney will use the summit to also press Xi on longstanding issues of political detainees and rights violations, cautioning that Beijing officials are likely to use Carney’s reputation to “burnish” China’s own credentials.

“There is a belief that because China is big, it must offer vast commercial opportunities. But few foreign firms reliably make profits there that they can repatriate. Most of what Canada sells China is energy and commodities,” says Kovrig. “Beijing’s power depends on fear, and its legitimacy rests on myths. We can push back against all of that. We can and we must.”

1 month ago

64

1 month ago

64