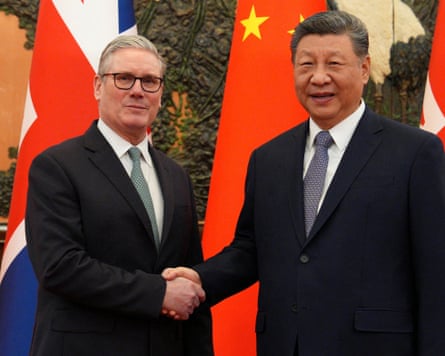

Keir Starmer’s tentative pivot to the Dragon Throne has played well in Beijing, though not in Trumpland. That’s partly because, like other needy western leaders, Britain’s prime minister did not dwell on awkward subjects such as human rights abuses, the Jimmy Lai travesty, spying and Taiwan. But in talks with President Xi Jinping, one vital issue was avoided altogether and should not have been: China’s dangerous, unexplained, secretive and rapid buildup of nuclear weapons.

More than the climate crisis, global hunger, Kaiser Trump’s Prussian militarism and the ever prevalent threat of pandemic disease, the uncontrolled proliferation of weapons of mass destruction is the most immediate, existential threat to humanity. Last week, the Doomsday Clock advanced to 85 seconds to midnight – closer to Armageddon than ever before. “Nuclear and other global risks are escalating fast and in unprecedented ways,” warned the clock-watchers, via the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Nuclear disarmament diplomacy is at a standstill globally. Consensus on collective future action is again expected to elude April’s non-proliferation treaty (NPT) review conference in New York. On Thursday, New Start, the last remaining arms control treaty limiting US and Russian strategic nuclear forces, will expire. Meanwhile, a scary international nuclear arms race is raging unchecked, as detailed in the 2025 report of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri).

Nearly all the nine nuclear-armed states – the US, Russia, China, France, UK, India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel – are pursuing “intensive nuclear modernisation programmes”, Sipri reported, including new weapons such as hypersonic missiles and “useable” low-yield tactical nukes. Nuclear testing may soon resume. “Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,241 warheads in January 2025, about 9,614 were in military stockpiles for potential use,” Sipri said. Of these, the US and Russia possess about 90%.

With an estimated 600 warheads, China lags behind – but it’s catching up quickly. “China’s nuclear arsenal is growing faster than any other country’s, by about 100 new warheads a year since 2023 … [It] could potentially have at least as many ICBMs [intercontinental ballistic missiles] as either Russia or the US by the turn of the decade,” Sipri calculated. Beijing offers no explanation or rationale for this dramatic surge – and rejects multilateral arms control talks.

An official white paper, published by China in November, restated its position that countries with the largest nuclear arsenals must make the first move, by unilaterally making “drastic and substantive reductions”. Until then, it said, China would keep its own nuclear capabilities “at the minimum level required for national security”. The paper conveniently omitted to say what that level is.

China’s criticism that the US and others ignore their NPT commitment to pursue disarmament is accurate, albeit hypocritical. It is on stronger ground when voicing objections to Donald Trump’s proposed multilayered, Greenland-related Golden Dome missile shield that could, if it ever materialises, dangerously upset the balance of terror.

Despite its current advantages, the US is worried. The Pentagon warned in December that “China’s historic military buildup has made the US homeland increasingly vulnerable”. It highlighted what it called a more attack-ready, “hair-trigger” nuclear posture, and claimed about 100 ICBMs were recently installed in silos in northern China. It also said Beijing was testing its ability “to strike US forces in the Pacific”, potentially crippling future US military assistance to Taiwan. “China expects to be able to fight and win a war on Taiwan by the end of 2027,” the Pentagon said.

What is Xi up to? China’s nuclear weapons drive could be just a question of status. Maybe Xi simply wants to match (or surpass) the US and Russia. Maybe he is genuinely fearful of being attacked. He told Starmer that “rampant” powers, meaning Trump, were following “the law of the jungle”. Or maybe, considering his legacy, Xi believes nuclear muscle-flexing (or worse) could help him conquer Taiwan and fulfil his ambition to make China the leading superpower.

Xi has acquired emperor-like sway after 13 years at the top. But he is also an insecure, fallible and unimaginative politician not immune to global trends and pressures. On the one hand, he sees Trump’s US upgrading nuclear weapons, trashing key arms control pacts such as the 1987 intermediate-range nuclear forces treaty, and attacking non-nuclear Iran and Venezuela on a whim. On the other hand, he sees an ally and fellow dictator, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, threatening nuclear war with the west as he tries to illegally seize Ukraine. It must be tempting to follow that example.

Disturbing, too, is the suspicion that, despite appearances, Xi may not be wholly in control of China’s armed forces. His sensational sacking last week of Gen Zhang Youxia, second only to himself in the military hierarchy, remains a mystery. Zhang, a grizzled veteran, is supposedly accused of disloyalty to his less war-experienced boss – and of leaking nuclear secrets to the US.

Is it possible the two men disagreed over Xi’s bullishly confrontational nuclear and Taiwan policies? Xi previously purged rocket force commanders, but is still apparently struggling to pull the generals into line. In a cold war echo, Dr Strangelove’s disconcerting question recurs: whose finger on the button?

Whatever China’s president is thinking, these are alarming times for anyone worried about global thermonuclear war – which should be everyone. Starmer’s talks with Xi reportedly included Chinese threats to UK national security. What bigger threat is there than proliferating nuclear weapons? Yet as far as is known, he did not raise the issue.

Starmer’s silence is unsurprising. Under his leadership the UK, too, is expanding its nuclear strike force, by buying US F-35A nuclear-capable fighter jets. And it is reportedly allowing the US to store nuclear bombs at RAF Lakenheath for the first time in 20 years. Britain is in no position to criticise. On the contrary, its unspoken message to Xi is stark: bombs away!

-

Simon Tisdall is a Guardian foreign affairs commentator

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4