It has been more than six decades since Eiko Kawasaki left Japan to begin a new life in North Korea. Then 17, she was among tens of thousands of people with Korean heritage who had been lured to the communist state by the promise of a “paradise on Earth”.

Instead, they encountered something closer to a living hell. They were denied basic human rights and forced to endure extreme hardship. Official promises of free education and healthcare plus guaranteed jobs and housing had been a cruel mirage. And to their horror, they were prevented from travelling to Japan to visit the families they had left behind.

But this week, after years of campaigning, four settlers who had escaped to Japan secured justice of sorts, when a court in Tokyo ordered the North Korean government to pay each of them at least 20m yen (£94,000) in compensation.

Between 1959 and 1984, more than 90,000 people, mostly zainichi – the name for people of Korean descent who live in Japan – became the victims of an elaborate North Korean scheme to recruit workers and deal a propaganda blow to the north’s former colonial occupier. A few, like Kawasaki, managed to flee and alert the world to what critics of the scheme say amounted to state-sanctioned kidnapping.

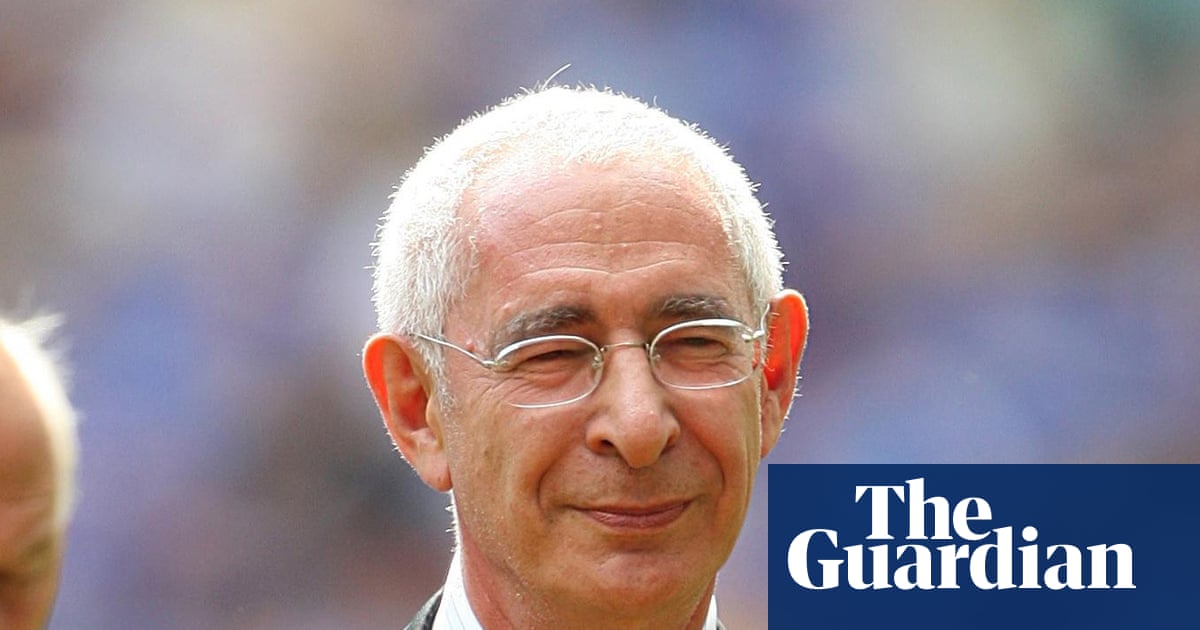

Kawasaki, 83, who said she was “overwhelmed with emotion” after the verdict, conceded that she and her fellow plaintiffs were unlikely to see a single yen. The Tokyo high court has no way of enforcing the ruling in the case, in which it symbolically summoned the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, to testify.

“I’m sure the North Korean government will just ignore the court order,” she said.

Kenji Fukuda, a chief lawyer for the case, said the most realistic option to retrieve the money was to confiscate North Korean assets and property in Japan. The plaintiffs, who launched their action in 2018, are among an estimated 150 people to have escaped from the programme in the North and returned to Japan.

The regime in Pyongyang, with the support of the Japanese government and help from the International Committee of the Red Cross, had promised ethnic Koreans a new life in a socialist paradise, with free public services and a higher standard of living.

The Japanese government and the Red Cross were not targeted in the compensation suit.

This week’s verdict was the first time “a Japanese court exercised its sovereignty against North Korea to recognise its malpractice”, Atsushi Shiraki, one of the lawyers representing the plaintiffs, said of the “historic” ruling.

Kanae Doi, the Japan director of Human Rights Watch, hailed the ruling as “one very important, successful example of attempts to hold North Korea accountable” for its international crimes.

Under the programme, those suspected of disloyalty “faced severe punishment, including imprisonment with forced labour or as political prisoners”, according to the group. The initiative was backed by the Japanese government at the time, with the media describing the programme as humanitarian and aimed at Koreans struggling to build a life in Japan due to widespread discrimination in housing, education and employment.

Many had been taken to Japan against their will to work in mines and factories during Japan’s 1910 to 1945 colonial rule of the Korean peninsula. The emigrants included 1,830 Japanese women who had married Korean men.

Kawasaki, a second-generation zainichi who was born in Kyoto, boarded a ship to North Korea in 1960 after being persuaded by promises of utopia made by the pro-Pyongyang General Association of Korean Residents in Japan – the North’s de facto embassy.

Instead, the plaintiffs claimed, the regime had wanted to attract ethnic Koreans, especially skilled workers and technicians, to address a labour shortage.

Kawasaki realised she had been deceived as soon as she arrived at a North Korean port, where she was greeted by hundreds of clearly malnourished people covered in soot. She stayed for 43 years until 2003, when she defected to Japan via China, leaving behind her adult children.

One of Kawasaki’s daughters and her two children have since escaped from North Korea, but she has had no contact with her other children since the regime sealed the country’s borders in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“I don’t even know if they are still alive,” she said.

Agence France-Presse contributed to this report

3 hours ago

4

3 hours ago

4