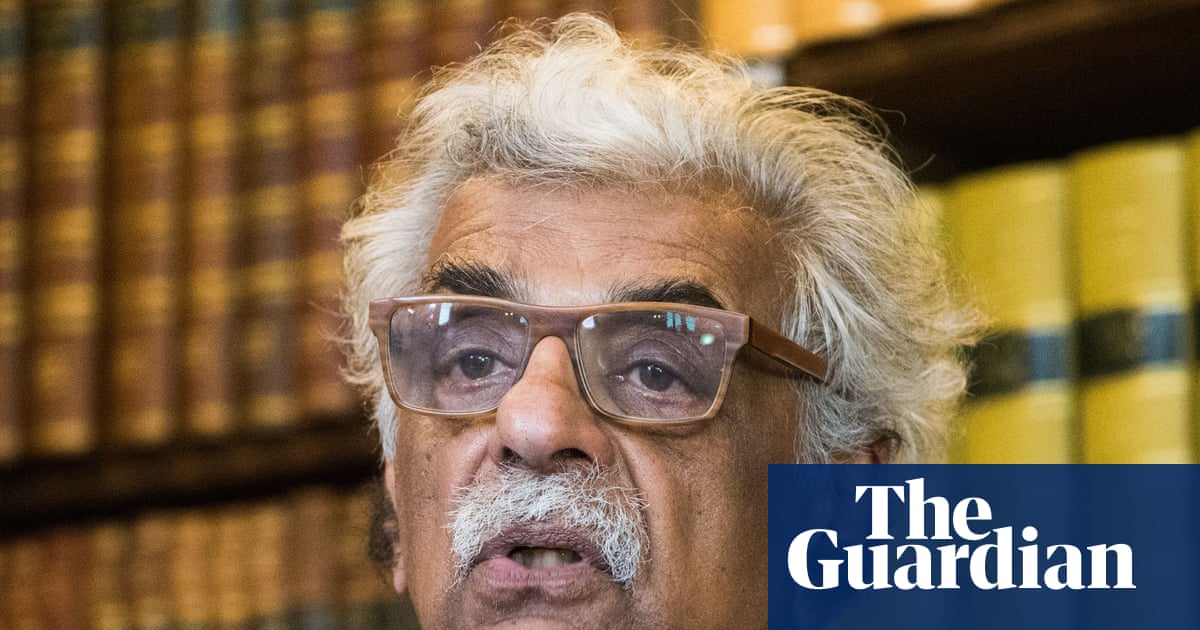

The big bloke in the khaki suit speaks quietly these days. We are nestled in the corner of Ted Milton’s studio above a rehearsal space in Deptford, London, cocooned by record boxes, poetry books, plus a single big, bright suitcase, and I have to nudge the recorder closer to pick up his voice. Milton – a saxophonist, poet, countercultural survivor and one-time avant garde puppeteer – is 82, and uses a couple of sticks to get around, yet he is once again going on the road across Europe with his long-running band Blurt, as well as releasing a new album with his duo the Odes.

Today, he is making record covers destined for the tour merch table with the help of his old woodblock setup. “That orange suitcase?” he points across the desk. “I just bought it.” He booms out a massive laugh, as if to prove he still has the lung power to command a room. “I’m a fetishist about luggage. I know how to survive touring. Haha!”

At many gamechanging moments in British postwar culture, Milton was skulking in the background somewhere, with mischief not far away. He recalls sharing taxis with William S Burroughs when the Beat godfather came to London in the early 1960s; he was described as a visionary by old drinking buddy Eric Clapton; his puppet show crashed its way into the Monty Python universe by being featured in Terry Gilliam’s 1977 film Jabberwocky; a legendary lost promotional film for Pink Floyd’s 1967 song Scream Thy Last Scream is rumoured to feature Milton’s overcoat in a leading role via the wonder of animatronics. And there is no band quite like Blurt, a bass-less trio of drums, guitar and Milton’s horns and vocals throwing down raucous, jazzy blowouts. “The groove they had was utterly fabulous,” says long-term fan Graham Lewis, of post-punks Wire.

Now, in the autumn of a long and sometimes outrageous life, the tables have been turned by Milton’s own family. He was married three times and had five children, the most recent when he was nearly 70, and a new film by son George Milton, The Last Puppet Show, aims to explore his father’s work and sometimes fraught relationships via the ingenious medium of his newly reanimated puppets. “It’s like a therapy session for kids,” he says of the film, cautiously. It’s your family confronting you with their point of view, I say. “That’s what I’m afraid of.”

Milton had a fragile relationship with his own parents, which laid seeds that flowered throughout his rebellious career. “My parents moved to west Africa when I was 11 and I went to a boarding school,” he recalls, which brought independence, but also repression and bullying, and he found solace through music. “I had a Dansette record player – Elvis, Carl Perkins, Little Richard.” But his other safety valve was disobedience. “I was looking to disrupt classes. Just be an arsehole, you know?”

He dabbled with art studies in Cambridge, and also the city’s jazz scene, before eventually falling in, quite literally, with the London bohemian set. “I went down to this jazz festival. I was rescued from lying in the mud by a group of beatnik looking people including [poet] Pete Brown. They took me back to London.” Brown encouraged his poetry, which even made it into The Paris Review in 1963. As Milton admits, he sometimes invoked the vocation of struggling poet simply to cadge drinks from strangers.

By the middle of the decade, Milton was living with girlfriend Clarissa in “a period of bohemian debauchery in Long Acre [Covent Garden]. Eric used to come round there quite a lot.” This was Eric Clapton, who recalls in his autobiography how Milton would spin Howlin’ Wolf and channel the music into dance and acting: “I understood how you could listen to music completely and make it come alive … it was a real awakening,” he wrote. Milton never lost this knack for performance. But whereas his old mate Pete Brown worked as lyricist for Clapton’s Cream, Milton reckons he passed up similar opportunities for Pink Floyd, whose managers Andrew King and Peter Jenner were also on the scene.

“If success was presented to Ted on a silver platter, he’d piss on it,” declares Roger Law, co-creator of Spitting Image. He’s at home in Norfolk at a kitchen table piled with books and illustrations, including Milton’s rough-hewn poetry pamphlets. The pair first met at the Cambridge School of Art and raised hell together, and linked up once again in London, sharing their dark sense of humour and appreciation for the absurd. “If you talk to Ted,” says Law, recalling their benders together, “you can’t tell the surreal from the reality.”

In the late 1960s, Milton took a post at a puppet theatre in Wolverhampton. “Then I moved to glove shows.” He mimes a Punch & Judy style performance with his hands. “It’s a whole different dynamic: violence. So I moved to that. I call it performance animation.” Law lauds Milton’s uncanny ability to bring puppets alive; the man behind Spitting Image should know. But for Milton, “puppets’ eyes are dead. They don’t feel challenged, they’re not afraid. This gives you this unrecognised but really potent possibility to get into people, and you can go to places in their head they don’t want you to.”

Milton’s skill in puppetry – showcased on Brighton’s West Pier, and then to numerous school audiences across Europe – led to some of the strangest support slots in 70s rock music, for Clapton and Ian Dury among others. Milton compares it to the urban myth of salesmen hardening themselves up by hawking peanuts on the street. “I was doing support for Clapton [in 1976], we were doing a performance in the round. I got the puppet theatre out there, the puppets are this big – ” he holds his hands a small distance apart “– and we’re talking about 1,000 people. Immediately, a roar comes up: ‘fuck off!’” Dury, meanwhile, would sometimes come to the stage to ask the audience to cool it.

But Milton’s outrageous, profane performances, with their anti-authoritarian message and Brechtian aesthetic, featuring characters such as Deepthroat Porker, Constable Nosey Parker and The Egg Dog, eventually gained a rep. Tony Wilson featured Milton’s puppetry on his groundbreaking So It Goes TV show in 1976, which caught the attention of Graham Lewis and Colin Newman, soon to be of post-punk band Wire. The puppet show slotted seamlessly into the violent medieval anarchy of Gilliam’s film Jabberwocky. When Milton then picked up a saxophone a few years later and formed Blurt, Wilson made them one of the first bands from outside Manchester to feature on his Factory Records label, and Wire invited them on to their bills. Milton’s subversive art had found a new home in the post-punk era.

Milton is a born performer, and Wire’s Lewis was immediately hooked: “Blurt were totally captivating,” he enthuses. A 1984 solo Milton track, Love Is Like a Violence, would even become an unlikely floor-filler at Glasgow’s hip Optimo club night in the 2000s. Although Blurt bounced between many record labels over the decades, Milton always made his way back to the spotlight eventually.

He’s very much front and centre of The Last Puppet Show: the film is a reckoning with the man Milton used to be, which for his associates was a driven artist, and for his family a sometimes wayward father. A chunk of the budget is intended for creating a new set of puppets to dramatise its scenes; Milton says the old ones were either sent to Alaska, or symbolically burned. “I don’t suppose I made any attempt to make any concessions to anybody anywhere along the line,” he admits, looking back on his wilder days. “One person beat me up.” I ask who it was, and it turns out to be one of his own bandmates.

While Milton’s anti-authoritarian streak remains as strong as ever, age has now forced him to start making compromises. “The last couple of shows I’ve had to do sitting down, which I really dreaded. But actually it kind of opens up a different dynamic,” he says, looking forward as ever to the next gig. “It seems to make things more concentrated somehow.”

I ask what he thinks it was about his performances that gripped Eric Clapton all those years ago, and whether he’s the same person now. “I think we’re talking about charisma. And charisma is a form of psychosis, to my mind.” He cites Alice Miller’s book The Drama of the Gifted Child, whose thesis holds that children are often forced to suppress their authentic selves, to support his point.

“This kind of intense self-consciousness has abated, mercifully,” he reflects, with a more easy-going perspective brought by age. “One person described it as feeling like you’re walking about on stilts all the time, and that’s it – every movement it’s like someone looking at you.” In other words, you felt like a performer all of the time? “Yeah. I’m not like that any more. Hahaha!”

3 hours ago

7

3 hours ago

7