Scientists claim to have “rejuvenated” human eggs for the first time in an advance that they predict could revolutionise IVF success rates for older women.

The groundbreaking research suggests that an age-related defect that causes genetic errors in embryos could be reversed by supplementing eggs with a crucial protein. When eggs donated by fertility patients were given microinjections of the protein, they were almost half as likely to show the defect compared with untreated eggs.

If confirmed in more extensive trials, the approach has the potential to improve egg quality, which is the primary cause of IVF failure and miscarriage in older women.

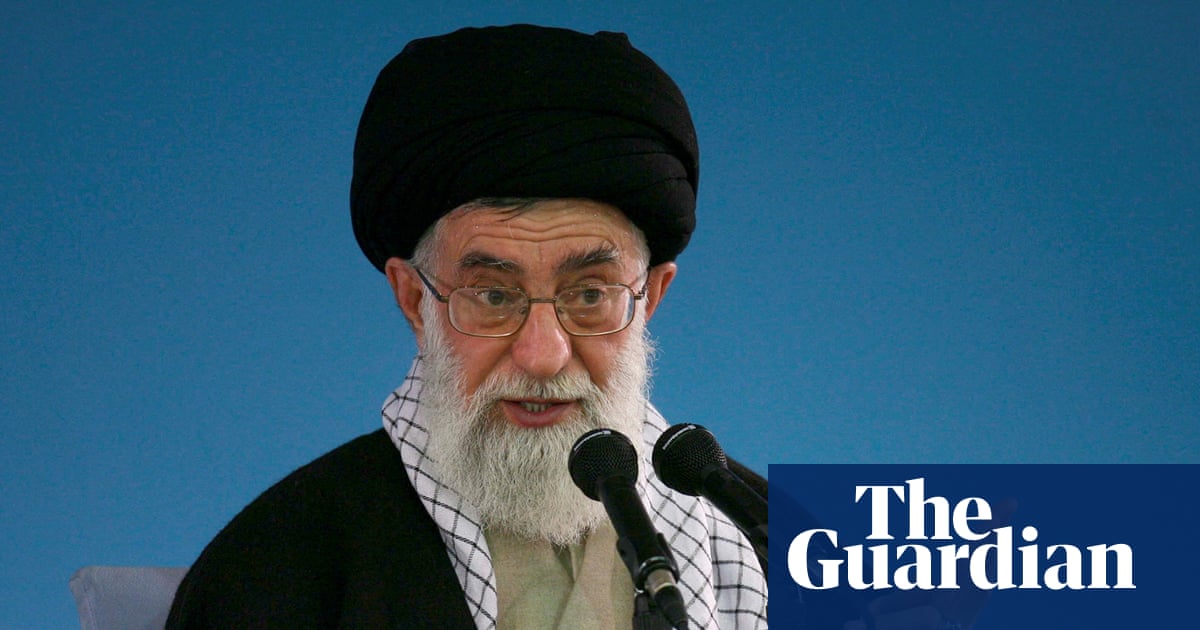

“Overall we can nearly halve the number of eggs with [abnormal] chromosomes. That’s a very prominent improvement,” said Prof Melina Schuh, a director at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Göttingen and a co-founder of Ovo Labs, which is aiming to commercialise the technique.

“Most women in their early 40s do have eggs, but nearly all of the eggs have incorrect chromosome numbers,” added Schuh, whose lab has been investigating egg biology for the past two decades. “This was the motivation for wanting to address this problem.”

The findings will be presented at the British Fertility Conference in Edinburgh on Friday and have been published as a preprint paper on the Biorxiv website.

The decline in egg quality is the main reason IVF success rates drop steeply with female age and is why the risk of chromosome disorders such as Down’s syndrome increases with maternal age. For patients under 35, the average birthrate for each embryo transferred in IVF treatment was 35%, compared with just 5% for women aged 43-44, according to the most recent UK figures. The average age of fertility patients starting treatment for the first time in the UK is now over 35.

Dr Agata Zielinska, a co-founder and co-CEO of Ovo Labs, said: “Currently, when it comes to female factor infertility, the only solution that’s available to most patients is trying IVF multiple times so that, cumulatively, your likelihood of success increases. What we envision is that many more women would be able to conceive within a single IVF cycle.”

The latest approach targets a vulnerability in eggs linked to a process called meiosis, in which sex cells (eggs or sperm) jettison half their genetic material so they can join together to make an embryo.

In eggs, this requires 23 pairs of X-shaped chromosomes to align along a single axis in the cell. On fertilisation, the cell divides causing the chromosome pairs to be – ideally – neatly snapped down their centres to create a cell with precisely 23 single chromosomes from the mother, the rest being delivered by the sperm.

However, in older eggs the chromosome pairs tend to loosen at their midpoint, becoming slightly unstuck or detaching entirely before fertilisation. In this scenario, the X-shaped structures fail to line up properly and move around chaotically in the cell, so when the cell divides they are not snapped symmetrically. This results in an embryo with too many or too few chromosomes.

Schuh and colleagues previously found that a protein, Shugoshin 1, which appears to act as a glue for the chromosome pairs, declines with age. In the latest experiments in mouse and human eggs, they found that microinjections of Shugoshin 1 appeared to reverse the problem of chromosome pairs separating prematurely.

Using eggs donated by patients at the Bourn Hall fertility clinic in Cambridge, they found that the number showing the defect decreased from 53% in control eggs to 29% in treated eggs. When they looked only at eggs from women over 35 years of age, a similar trend was seen (65% compared with 44%), although this result was not statistically significant, which the scientists said was probably due to them only having treated nine eggs in this age range.

“What is really beautiful is that we identified a single protein that, with age, goes down, returned it to young levels and it has a big effect,” Schuh said. “We are just restoring the younger situation again with this approach.”

The approach would not extend fertility beyond menopause, when the egg reserve runs out.

Aside from intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), there are not currently any treatments involving microinjections into eggs, but the team does not anticipate safety issues and are in discussions with regulators about a clinical trial. An important question will be whether the apparent improvements in egg quality results in embryos with fewer genetic errors.

Dr Güneş Taylor, of the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the research, described the findings as “really promising”.

“This is really important work because we need approaches that work for older eggs because that’s the point at which most women appear,” she said. “If there’s a one-shot injection that substantially increases the number of eggs with properly organised chromosomes, that gives you a better starting point.”

1 month ago

72

1 month ago

72