“Someone who worked a lot with rock stars told me that the age that they become famous is the age they stay for the rest of their life. I thought: ‘That doesn’t bode well for me,’” Joe Cole says ruefully. “I was in the public eye at 16 and thrust in front of the media. You grow up, you become a dad, but you’re still a footballer. And then, all of a sudden, it stops but your whole identity is still wrapped up in it.”

The former West Ham, Chelsea and England footballer, a gifted maverick who always felt a man out of time, playing a game years ahead of most of his contemporaries, smiles when I ask how old he feels now: “Forty‑four. I’m 44 [this Saturday]. My wife will laugh if she reads this, but you emotionally mature quite quickly as a footballer.”

Cole was a teenager from Camden, living on a council estate, when he was splashed across the front page of the Sunday People. The headline roared: “£5,000 A Week And He Is Just 16!”

As he notes in his evocative new book, that inaccurate article made people think he “was spoilt, overpaid and had too much too soon. The truth was that I could have earned many multiples of that if my parents had manipulated the interest in me from every big club in England.”

Cole shakes his head. “That’s when I realised: ‘Oh, shit, things can change towards you.’ Even if you wake up the next day and feel the same, you notice different behaviour in people. I remember a moment at West Ham when I was 18 and I can still picture the fellow’s face. He wore a black leather coat and he was screaming abuse at me at Upton Park. He was in his mid‑40s and spit was coming out of his mouth. People don’t understand that footballers need a certain maturity to deal with that.”

He had been such a prodigy that, in 1994, Alex Ferguson called Cole’s adoptive father to say that he knew 13-year-old Joe was a Chelsea fan but would he like to be United’s mascot for the FA Cup final against Chelsea? George Cole asked his son if he really wanted to join United. When Joe said no, they turned down the offer.

George was jailed twice but he had an integrity which meant he and his wife, Susan, dealt firmly with unscrupulous agents. “I didn’t know how good I was because when I was eight I’d be playing with kids of 13,” Cole says. “But there’s an insidious financial element when it comes to children. My mum and dad got offered lots of cash and holidays but they had morals.

“My dad couldn’t read and he’d never signed a contract in his life. In his world, your word is your bond. In football that’s very rare. Anything which generates the money you get in football means the parasites come.”

The prodigies seem even younger now. Cole nods appreciatively when I mention 15‑year‑old Max Dowman, who has played for Arsenal in the Premier League and, this week, became the youngest Champions League footballer: “He’ll be well protected. His dad is a businessman and we’re in a different era.”

Does he feel concern that Dowman’s protective bubble will make it difficult for him to live an ordinary life – unlike Cole who ran free as a kid? “Max will probably become a top, top player. His talent is supreme but I hope he’s got other interests outside football, a nice balance to his life. I always tell my two sons, who want to be footballers, to have an identity outside the game.”

As a boy Cole played football on the playground, and in concrete cages, with joy: “I did not play an organised game with refs and shin pads and corner flags until I was about 11.”

So no scouts were watching? “No. Until I was 11 I was completely away from it all. Then I started to play for Paddington Rec. They were terrible. I had to play defence because it was the only time I’d get the ball. I’d try and dribble past everyone. We’d lose 10-2 and I’d score two.”

The scouts came flocking when Cole moved to a far better team. By the time he had been spotted by the Football Association, and accepted a two-year scholarship at Lilleshall’s school of excellence, Cole knew that he was different to the coaches and most players. He hated the rigid 4-4-2 and clunky long-ball archetype of the English game and yearned to play football with the sophisticated panache of Barcelona.

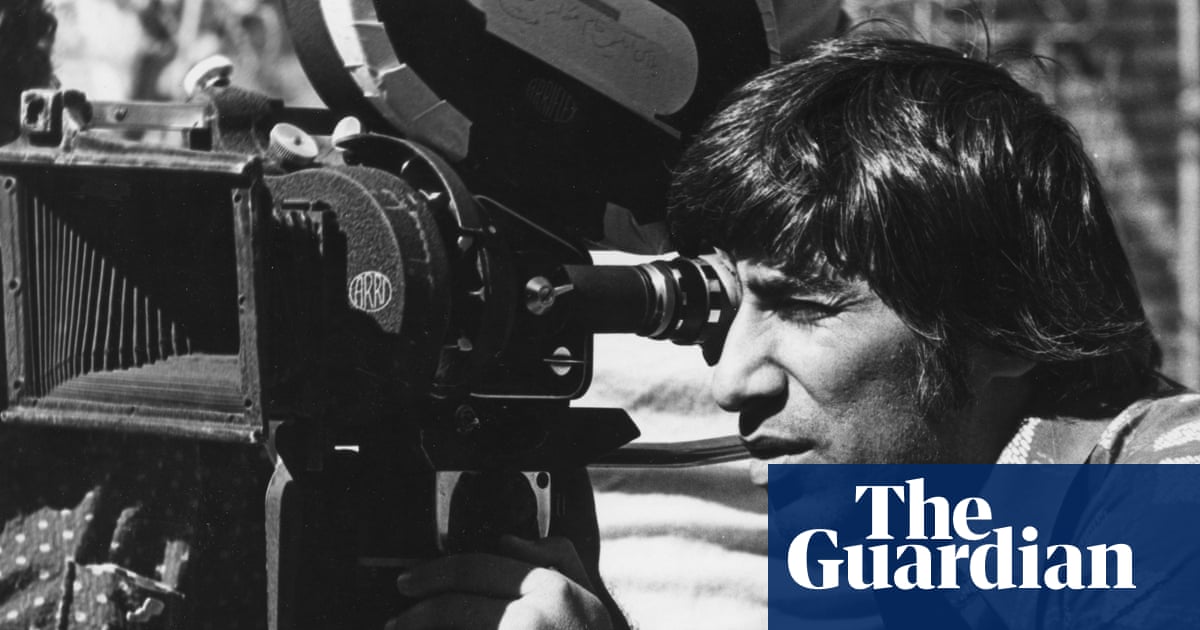

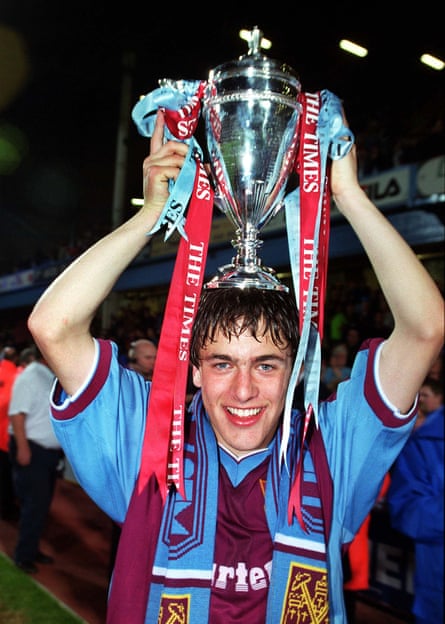

He brought such verve to West Ham, where he made his Premier League debut at 17 in 1999. There is a lovely passage in his book where Cole recalls “the sound of thousands of seats snapping shut as people stood up when I slipped past an opponent and ran at goal. I believe strongly that stadiums sounded different before we all had phones distracting us. The fans were in the moment. There was an immediacy of reaction that feels slightly delayed now, or an intensity that has had the edges knocked off.”

His eyes widen as he says: “It was a sound of approval. It’s like a young actor saying they crave the sound of applause. As a footballer who liked to play in an artistic way I knew that sound was only for players who can do things differently. But we don’t hear that sound any more. We’re all on our phones too much. I’d love to see a stadium ban on phones.”

Cole was in the first wave of transfers Roman Abramovich sanctioned when the Russian oligarch bought Chelsea in 2003. That move ushered in Cole’s golden years and at Chelsea he won three Premier League titles, two FA Cups and played in a Champions League final. But as money has sanitised football, does Cole still think Abramovich’s arrival was good for the game?

“It’s a good question. Obviously the Premier League has allowed me to live a wonderful life but we need to protect football and never forget it’s a community-based game. That’s why West Ham fans are up in arms. They’ve lost their home and feel disconnected from the club.”

Cole sometimes felt disconnected from football because so many managers saw him as “a luxury player” – even though his defensive work and passing efficiency helped to make him a key member of José Mourinho’s serial-winning Chelsea team.

“My attributes were so much more suited to today’s game,” Cole suggests. “But I didn’t get downhearted. I wanted to win loads of trophies and be the best I could be.”

Cole felt an affinity for European football but says: “I needed to make it work in England. When I speak to young footballers it blows their minds that, in my time, you had to be left-footed to play on the left, right-footed on the right, and all you needed to do was beat a man and cross it. It shows how backward we were as a nation and it stunted the development of English football.”

after newsletter promotion

What does Cole think of the current reliance on set-piece goals and long throws? “There’s been a 9% increase in set-piece goals this season which is huge. Some bright spark has gone: ‘Let’s try the long throw again.’ They’ve worked out that none of these centre-halves today know how to deal with it – like they did 20 years ago – because the game’s changed. Now they’re having to readjust.”

Does it make his heart sink? “No. I like to play football the right way but I would look at my team like my house when you’re locking doors and windows at night. You don’t want to leave a window open.”

Cole is intrigued by management and he considers Mikel Arteta to be the most interesting manager in England today. “[Arsenal] is his first job and he’s done it slowly, almost like he’s putting a puzzle together over the years. You hear this nonsense that he’s only won one trophy in six years. Arsenal were on the floor when he took over. I always liken a football club to steering a cruise ship. He’s had to do it slowly so I admire him greatly.”

I ask Cole where he would like to be 10 years from now. “I’ll be 54. I’m a firm believer that, after playing for some great clubs and [56 times] for England, you can will things into existence. I’ve always tried to dream big. So my dream job would be to manage England one day.”

Cole makes me laugh when he looks around and admits: “I don’t know how I’m going to do it sitting here in a Mexican restaurant [near Oxford Circus]. But I’d love to be Thomas Tuchel going into the World Cup with that group of players.”

He believes that England should have won the World Cup in 2006, when he was part of that team, and thinks Tuchel has a realistic chance of winning the tournament next year. Cole makes nuanced arguments about the way in which Tuchel is moulding a cohesive squad, and how Jude Bellingham and Cole Palmer should still be picked, and it’s clear that he has the tactical intelligence and knowledge to try to find his way in management.

He has just stopped playing Sunday League football so he can support his boys at their matches: “I miss it badly. If the kids didn’t play on Sundays, I’d still be turning out because football makes me feel free.”

Cole is amusing as he relates how many Sunday morning promotions and cups his team won – while confirming that footballers on Hackney Marshes now try to play out from the back. Of course some defenders just wanted to hack him down because he’s Joe Cole. “But I try and pre-empt that and kill them with kindness. Like in life, 95% of people I’ve played against were good as gold. And I know when someone is out to kick me. I see them coming even before they’ve thought about it.

“If they’re really out to do me I just jump up and on the way down they get studs on the shin or an elbow in the face. ‘Sorry mate, you all right?’ But, mostly, Sunday League is brilliant.”

His eldest son, Harry, is at Brentford’s academy. “My youngest son, Max, is also really talented but I wouldn’t want him at an academy yet. He’s only 10. I held Harry back because he got invited to trials and I said: ‘No, he’s happy playing with his mates.’ The most crucial thing is he’s got other interests. He cooks and gardens.”

Cole grins when I ask if he also gardens. “No. We live in Chelsea and at the front of our house Harry and my wife plant tomatoes and fennel. I often sit outside because there’s a nice suntrap. I enjoy a cup of tea and lovely comments from the old Chelsea ladies.”

The former footballer really does sound as if he has found a new identity as his smile widens. “I say: ‘Yes, all my own work. Feel free to pick a tomato if you want.’ I claim it.”

Joe Cole’s Luxury Player (Seven Dials) is published on Thursday. To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

1 month ago

47

1 month ago

47