For the sake of British justice, something has to give. Everyone knows that the courts are in crisis, that we can’t go on like this. Traumatised victims can’t keep being told that the earliest available date for a trial is 2029, so they’re either going to have to live with it hanging over them for another four years or drop out. (And nor can defendants put their lives endlessly on hold, worrying that witnesses’ memories will only fade with time.) Something obviously needs to change. But the idea that the only solution is to scrap jury trials in all but the most serious cases of rape, murder and other offences with sentences longer than five years – as a leaked letter from the justice secretary, David Lammy, suggests – should ring alarm bells nonetheless.

Anyone who has sat in a courtroom for long enough, never mind on a jury, will know that it isn’t exactly 12 Angry Men out there. Members of the public obliged to dispense amateur justice have the same flaws, limitations and tendency to fall asleep in the boring bits – or, as on one memorable occasion at the Old Bailey, repeatedly ask if the hot witness is single – as the rest of us, and unlike judges they aren’t obliged to give their reasons for sometimes baffling decisions. Juries are notoriously resistant to convicting in all but the most straightforward rape trials, and expert doubts raised over Lucy Letby’s murder conviction make a strong case for removing them from cases with very complex medical evidence. All that said, however, they’re absolutely vital to justice being seen to be done.

Public confidence in institutions depends, as the prime minister’s one-time legal mentor Lady Helena Kennedy KC put it this week, on public involvement in an establishment that can otherwise appear remote. Jury service is the only chance most people ever get to see the legal sausage getting made, and while the results aren’t always edifying, being excluded from the process seems even less likely to inspire confidence. Meanwhile for defendants and their families, the right to be judged by one’s peers – including people more closely resembling the person in the dock than the one in the wig – matters.

Even with an increasingly diverse judiciary, juries are seen as a safeguard against racism, as Lammy himself used to argue before getting this job: 12 people riddled with competing biases may paradoxically have a better chance of collectively cancelling out each other’s assumptions and blind spots than one however highly trained to be impartial.

And at the risk of sounding faintly paranoid, juries represent a safeguard against the politicisation of the courts that is not to be taken lightly in the current climate. Judges are appointed – a process much more easily hijacked by future governments of malign intent than the act of picking random names from a phone book.

Perhaps it would be worth overriding all those fears if juries were the main cause of gridlock. But when only a tiny 1% of criminal cases in England and Wales actually end up in front of one, at best this feels like a cover for the real problem: public reluctance to pay for the services we want.

As with NHS waiting lists and asylum seekers cooped up for years in hotels, the judicial backlog is the legacy of previous governments’ spending choices, for which this one is getting unfairly blamed. The system has gummed up thanks to the chronic underfunding of not just the courts but of other public services on which they depend. Long delays getting mobile phone data analysed or obtaining reports from probation officers and social workers before sentencing all add up, and so does the time wasted by defendants who don’t qualify for legal aid attempting to use ChatGPT to conduct their own defence.

The untold side of the story meanwhile is the growing complexity of the law – usually as a result of parliament satisfying public demands for “something to be done” – and more proactive policing of complex historical sexual abuse and exploitation, otherwise known as police and prosecutors doing exactly what society is asking of them, but without the funding to see it through.

after newsletter promotion

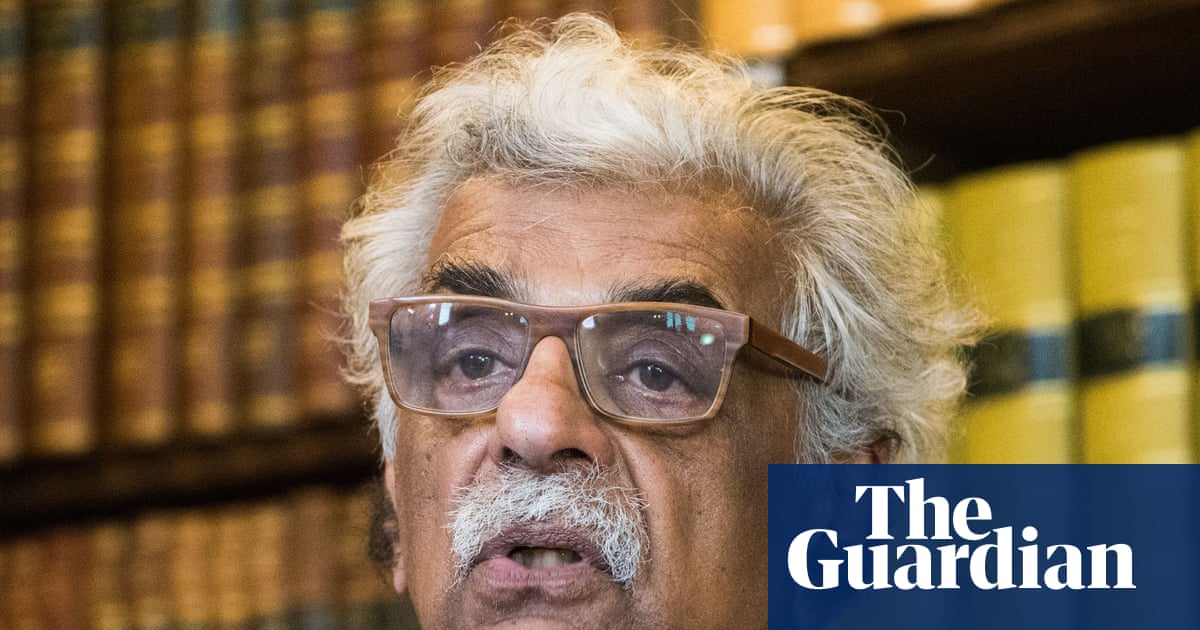

Lammy’s proposals follow a review by Sir Brian Leveson KC that proposed removing defendants’ right to request a jury trial in some “either way” cases (which can go either before magistrates or crown courts); creating a new juryless division of judges and magistrates for others; and allowing a judge sitting alone to hear some of the most serious cases if either the defendant so chooses or the judge feels the complexity of the case warrants it.

But as he makes clear in his report, Leveson’s terms of reference obliged him to “take account of the likely operational and financial context”, which is Whitehall-speak for: “There’s no money left, so don’t go getting ideas.” He did in good faith the job he was given, which was to find cheap ways of starting to cut the backlog and trust that eventually the cash would be forthcoming to finish the job. (Scrapping jury trials doesn’t save much money, but Leveson calculates it would free up 20% of court sitting time, allowing more cases to be heard within existing budgets.) It’s the same gamble underpinning Rachel Reeves’s budget this week – the hope that something will turn up before 2029, allowing harder choices to be avoided – with all the same potential risks and rewards.

Justice delayed is, as the saying goes, justice denied. Let’s hope justice on the cheap doesn’t become justice discredited.

-

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist

2 months ago

55

2 months ago

55