In early 2020, on the eve of lockdown, Phil Neville, then head coach of England, dropped Mary Earps from the squad.

For the first time ever, I began to feel something unimaginable; I felt disillusioned with football and unsure what I was doing in life, chasing this dream that was constantly in reach but never fully within my grasp. And then, abruptly, lockdown hit. And the world changed, at either the best possible time for me – or the very worst.

My life had been built around a structure for when I trained, ate and even when I slept for as long as I could remember. It was my scaffolding. Suddenly, after rarely ever having had more than a day off at a time, I could do whatever I wanted.

I threw everything I knew out the window and did all of it, in any measure, whenever I wanted, kidding myself that this break from the grind could do me good. I stopped answering my phone, watching friends’ and family’s names flash across the screen then waited for the backlight to dim as I returned to whatever I was watching on TV.

I barely moved from the sofa, shovelling down biscuits instead of meals, and developed horrific sleep patterns, watching the final episode of The Last Dance, the documentary series about Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls, then looking up to realise it was 5am.

I told myself that I was enjoying making decisions for myself for the first time in adulthood, choosing what I did with my time and what I didn’t.

In reality, I was taking the isolation we’d been forced into and letting it do its worst and it didn’t take long to realise that this whole situation was a dangerous invitation to demons.

My whole life I’d believed that vulnerability and huge floods of emotion were weakness, but now that the doors were closed I could be as vulnerable as I chose, on my own, away from everyone. It was like the times I used to cry in my bedroom over my frustration at my hunger to play.

The truth is, I was in pure survival mode but barely surviving at all.

I started drinking in a way I wasn’t used to. I put Echo Falls Summer Berries Vodka in the freezer and poured it out with diet lemonade and strawberries suspended in ice cubes, like another indulgent treat.

When I ran out, I’d go down to the local shop and stock up again while I queued for essentials like toilet roll.

On one of the many days that melted into the next, I remember going to the Tesco superstore round the corner where the queue was out the door and you had to follow social-distancing rules, two metres between each shopper, through every aisle of the store as you gathered what you needed. I slowly snaked that entire supermarket, not picking up a thing, until I got to the drinks aisle. I wasn’t drinking myself into oblivion but for someone who usually didn’t touch it at all, it felt too much and completely out of hand.

I’d never drunk like that in my life, but for now it was the perfect way of numbing, of not feeling, and that, I decided, was what I needed above all else.

Meanwhile, I was piling on pounds and annihilating my fitness, and that old body-consciousness about being big and bulky was back with an angry vengeance, so I stopped eating as much. Relying on junk food wasn’t making me happy anyway, so instead I underfed myself, which was just as destructive. I told myself I was experimenting with fuel, working out what my body needed, but that was nonsense. Not eating was also getting me drunk and therefore numbing my feelings quicker. For two weeks straight I ate nothing but soup, drank Echo Falls at night, and continued trashing my body and my self-confidence.

after newsletter promotion

I had withdrawn into a shadow of myself – and then become someone I didn’t recognise at all.

None of my behaviour was conscious. If it had been, I’d have been horrified by what I was doing to myself. And what I was doing to my friends and family, who must have been worried. With hindsight, I don’t judge myself at all for trying to get through in the way that I did, I was just putting one foot in front of the other so I didn’t give up and give in entirely. What I can see now is that I was probably struggling with depression or anxiety, maybe both. In the midst of those things it becomes hard to contextualise things, as much as you try. I understood the gravity of what was happening in the world around me but I couldn’t ignore what I was feeling. I simply didn’t have enough clarity to see all of it.

Football had always given me a purpose. It was the reason I’d been put on this planet. My whole identity was as an athlete and my only aim had been to be the best goalkeeper in the world. Now I wasn’t sure if I had anything left to work towards and weeks of solitude had given me all the space I needed, or dreaded, to question what it was that I’d committed my life to: this pursuit, this game, a career that didn’t seem able to give me anything back anymore.

Without football, I realised I didn’t fear anything any longer. Nothing. Not even death. It sounds strange to say that now, especially when death was such a real threat then for so many people fighting for their lives. But to me at the time I felt if I wasn’t going to achieve what I was meant to accomplish then what was there left to be afraid of? I lost the will to fight and, in some of those moments, I lost the will and the desire to live. For the first time in my life, I wondered if there was any point in me being here any longer. I don’t believe I was ever going to end it all but I thought, too many times, about how I could.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123, or email [email protected] or [email protected]. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org.

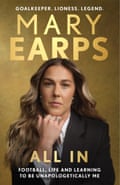

This is an edited extract from Mary Earps: All In by Mary Earps (Bonnier Books, £22). To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

1 month ago

62

1 month ago

62