What’s the difference between white and red miso, and which should I use for what? Why do some recipes not specify which miso to use?

Ben, by email

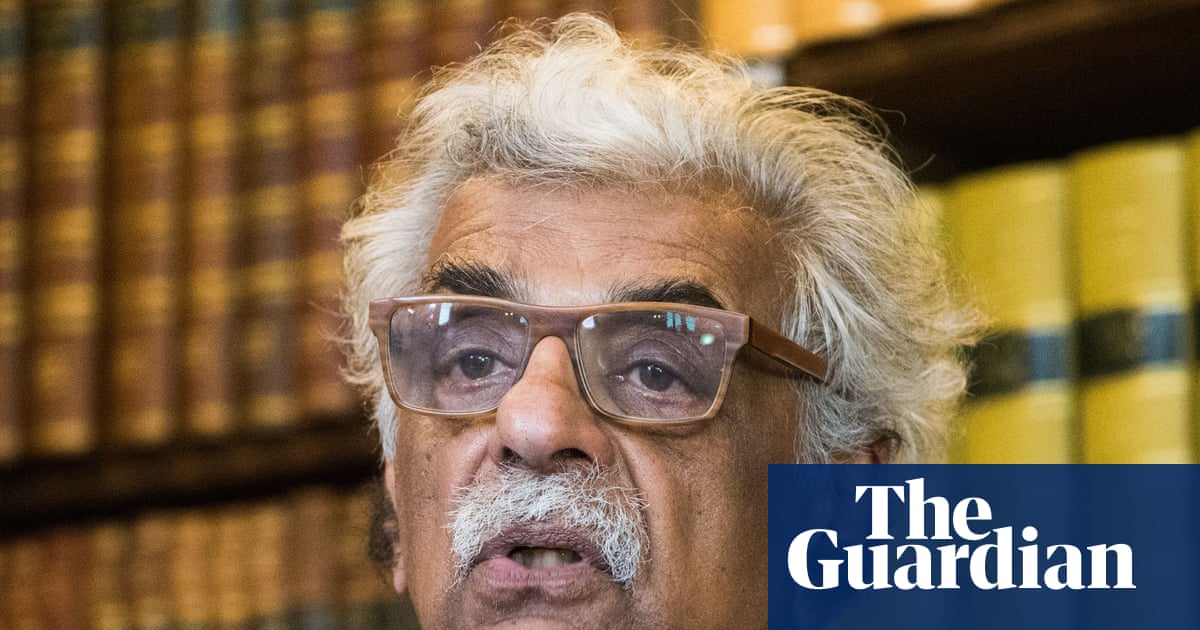

“I think what recipe writers assume – and I’m sure I’ve written recipes like this – is that either way, you’re not going to get a miso that’s very extreme,” says Tim Anderson, whose latest book, JapanEasy Kitchen: Simple Recipes Using Japanese Pantry Ingredients, is out in April. As Ben points out, the two broadest categories are red and white, and in a lot of situations “you can use one or other to your taste without it having a massive effect on the outcome of the dish”.

Salty, savoury miso is (usually) made by steaming soya beans, mashing them with salt and koji, then leaving to ferment. “And the age is what changes the colour,” says Anderson. “White miso is not aged for very long – three to six months – and so it retains that beany, beige/yellow colour and tastes fresher, while red miso is aged for six months or longer, resulting in a darker colour and more funk.” The parallel Anderson often draws is that of a mild cheese and an aged or mature cheese. “Gouda is a good example,” he says. “It can be quite mellow and salty, but as it ages it develops a buttery, caramelised flavour.”

As to which miso to use when, the general rule is: if you want to keep things light, use white; if you’re after something more savoury, something richer, then go red. “There’s a recipe in my new book for misotrone [AKA minestrone seasoned with miso] and that’s a good example of what miso can do to food,” says Anderson. “White miso accents the tomato’s acidity and freshness, but if you use red, you get a richer, more concentrated tomato flavour.”

Likewise, Emiko Davies, author of The Japanese Pantry, dollops red miso on top of fried or roasted aubergine, while lighter misos are for soups with clams or other seafood. Millie Tsukagoshi Lagares, author of Umai, meanwhile, leans on the latter to crank up dressings, marinades for white fish, and bakes or sweet treats (hello, miso caramel). But the other thing you could – and should – do, adds Davies, is mix your misos: “You can customise a more complex flavour – think of it like a blend.”

Other misos you might come across include shinshu (yellow) miso, which, happily, can offer the best of both worlds. “It has the right amount of savouriness and nuttiness,” says Tsukagoshi Lagares, and is best used for miso soup and sauces. Then, there’s sweet white miso, or sweet rice miso, which is “fresh and not very salty or funky,” notes Anderson, making it a good call for mild ingredients (think the classic Nobu miso marinated black cod). At the other end of the spectrum is hatcho miso, which is aged in open barrels for a minimum of 18 months, turning a very dark brown, and “has all these rich flavours, such as cocoa, Marmite and molasses”. And if you can find it, check out Anderson’s favourite category: nama miso, or unpasteurised miso. “It has an interesting, lively aroma that you don’t get from other misos,” he says, and it works like a dream as a marinade. “It’s some of my favourite stuff.”

-

Got a culinary dilemma? Email [email protected]

4 hours ago

8

4 hours ago

8