A psychiatric review of Larry Sultan, carried out by the military in 1969, described the American as an anxiety-prone individual who felt like a “left-out observer looking inside”. Sultan may not have been fit for service but, with that short phrase, the report identified the essential quality that would make him a great photographer of American domestic life.

The report is included in a new book, Water Over Thunder, published in collaboration with Sultan’s widow Kerry and son Max. In a career that began in the 1970s and lasted until his death in 2009 at the age of 63, Sultan was never confined to a single genre, but rather moved between documentary, fiction and appropriation. He photographed the ordinary middle-class homes of the San Fernando Valley in California rented out for porn shoots, made a portrait of Paris Hilton in his parents’ bedroom, and took underwater pictures of people learning to swim in San Francisco.

He photographed it all with a hazy familiarity and an eye for the idiosyncratic and ironic. “He hoped that by focusing on daily life,” Kerry once said, “he would capture something mysterious that was just out of view. When you slow life down, and look in between those big events that you think to capture, you see the stuff that people live every day, and that’s what really hits home.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1946 to Jewish parents, Sultan relocated to Los Angeles with his family in 1950 as part of the “postwar quest for a better life”, as the photographer puts it in a passage included in Water Over Thunder, the first publication devoted to his writing. His relationship with his father was complicated: “He was pissed that I was an artist and he gave me a hard time. He called me a loser.”

Water Over Thunder unfolds as an informal autobiography, piecing together Sultan’s reflections on his first forays into photography and his ideas about it, alongside personal ephemera, journal entries, letters, postcards and, of course, his images. It all adds up to an intimate and unprecedented portrait of the photographer, in his own words.

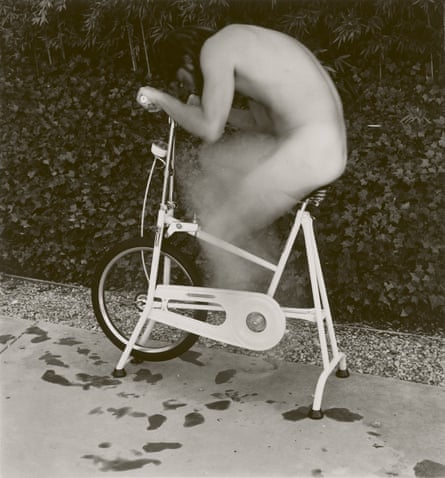

Sultan grew up in the San Fernando Valley, returning there to make The Valley, his porn set odyssey. In the course of more than 100 shots, taken from 1998 to 2004, he captured fabulously kitsch interiors of these rented-out homes, full of ornately carved wooden furniture and anodyne animal and nature paintings, along with zebra-print rugs and vases of fake flowers. Occasionally, we even glimpse naked actors, relaxing between shoots with rollers in their hair, as fully dressed crew members organise their equipment.

“Taylor is sitting in the shade completely exhausted,” he writes of one shoot he sat in on. “She is eating a piece of toast with raspberry jam. I can see that some crumbs have fallen on her naked belly. As if to apologise, she explains that she hasn’t eaten all day because she doesn’t like to eat before an anal scene.”

The Valley was a visually mesmerising, if faintly uncomfortable, reimagining of the stereotypical US home as a theatre for performed desire, yet Sultan makes you wonder if its various scenes are really so very different from the staged fantasy of modern American family life. “I feel like a forensic photographer searching out evidence,” he writes of The Valley. “I’m planted squarely in the terrain of my own ambivalence – that rich and fertile field that stretches out between fascination and repulsion, desire and loss. I’m home again.”

Sultan called home a “big influence” and all his major work was made in, and about, suburban California. In the 1970s, he moved from the valley to the Bay Area to study photography at the San Francisco Art Institute. “The times were so interesting,” he writes. “The streets were so interesting. So being a photographer allowed me to witness and to participate in a way that felt right for my blend of being alienated.”

It was an exciting time for photography in the US. The 1970s birthed the Pictures Generation, a group of New York-based artists spearheaded by Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince, who directed photography, film and performance at booming consumer culture. But San Francisco’s scene, Sultan writes, “bored me to tears”. He goes on: “I didn’t understand the language of academic critique, and I didn’t feel comfortable sitting in cafe culture.” Food was a different matter though. “I was interested in Bob’s Big Boy combo plates with thousand island dressing and french fries.”

Sultan befriended a fellow art institute student from San Fernando, Mike Mandel, with whom he shared a love of postwar pop, postcards, billboards and a “non-artful view of the world”. The two became collaborators and, with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, produced a groundbreaking, coolly subversive work called Evidence, published in 1977.

Considered one of the first works of conceptual photography, Evidence presents 59 uncaptioned black and white photographs. Over a period of two years, the pair combed through thousands of archival images belonging to government and corporate institutions, including General Atomic, Nasa, the US Navy and the Pacific Gas and Electric Company.

Taken out of their original context, these images of crime scenes, scientific experiments and engineering tests become bizarre and even poetic. A man wearing a bag on his head is set on fire; an astronaut does push-ups; men in hard hats stand in a sea of white foam. They’re images that capture the excitement of this dawning age of technological innovation and advancement – but also the human need to go forth, conquer and control.

Sultan was also willing to hold his own life up to scrutiny. His most famous work, Pictures from Home, depicts his ageing parents at home in the valley suburbs. They tinker with a vacuum cleaner, his mother dressed in bright pink socks and a matching hoodie. They play chess and argue in the driveway. His father, dressed in leggings, practises his golf swing in the living room, with its unforgettable avocado walls and matching carpet.

Sultan used his parents as a symbol for how the “Republicans had hijacked the family and family values and they had turned it into an ideological tool. I felt the family they were talking about was quite oppressive, and I felt that family was one of the most complicated, unnerving institutions. Yet it is the institution most of us believe in.”

The pictures have all the tenderness and affection of a family album, albeit without sentimentality. But they also speak of a disenchantment with the American dream and its impact on family dynamics. Sultan’s father was an orphan who, despite his working-class background, worked his way up to become vice-president of Schick Razors. But he lost his job in his 50s when the company was sold and never worked again.

Pictures from Home was the result of nine years spent photographing and interviewing his parents. They became de facto collaborators, although in Water Over Thunder, Sultan recalls his nerves on showing them his prints for the first time, carefully placing the most flattering ones at the top. “Even though I was going to show them pictures of themselves, I felt like I was about to say, ‘Let me show you what I really think about you’ – and reveal thoughts and secrets that I felt guilty for having. There was no doubt about it, I was a bad son.”

Way ahead of its time, Pictures from Home showed how private images could find a place in public, encouraging us to examine how we see ourselves and want to be seen. It also showed the healing potential of art. “It allowed me to resolve a lot of my issues with my family,” writes Sultan.

Water Over Thunder also tells us what things Sultan was drawn to, even including a list he jotted down of his five favourite films (No 1: sci-fi classic The Incredible Shrinking Man). Teaching was as important to him as photography. This career began at his alma mater in 1978, continuing at California College of the Arts, where he was a professor in the photo department for two decades.

It began as a way of supporting his photography but soon became an essential part of who he was. He fondly describes his students as “fellow travellers”. A teaching schedule reproduced in the book includes discussions of Nan Goldin as well as ballroom-dancing lessons.

Artist Carmen Winant, who was taught by Sultan, remembers him as a “deeply funny, kind, sharp and devoted teacher”. What about his photography and its influence? “He remains a giant,” she says. “Although he had many endearing qualities, the one that I remember most was his curiosity. He used to say, ‘Isn’t that endlessly fascinating?’”

3 hours ago

5

3 hours ago

5