It must have been an eerie sight when 35-year-old Diudonné Muka looked over his shoulder and saw a trail of people stretching as far as the eye could see. The line ebbed and flowed deep into the surrounding forest, a river of multicoloured clothing cutting through the green.

He saw countless women balancing trays of goods on their heads, babies on their backs, tightly wrapped in kikwembe cloth. Men and children carried whatever they could: chairs, rugs, blankets and sacks of food; anything that might still be useful.

“When war begins, you take what you can in your hands and run,” Muka says over the phone. Over the two-day, 21-mile (34km) trek, he heard a mix of languages, from Kiswahili to Kirundi Lingala and French. Livestock such as cows, goats and chickens were plentiful at first. Then, slowly, they disappeared.

There was only one sound that halted the family’s progress: bombing. The shelling was relentless, each side trying to outdo the other. “They bomb, and the others bomb back. Over and over again,” Muka recalls. “You would pass a house that had been hit and see dead bodies, and you thought: ‘I don’t want that to happen to me.’”

Some of the thousands walking alongside him in December were neighbours; others were complete strangers. All were fleeing the town of Luvungi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s South Kivu province, searching for whatever safety they could find. Both North and South Kivu have been engulfed by renewed conflict over the past three years, since the Rwanda-backed M23 rebel group re-emerged.

The group had captured Goma, the capital of North Kivu, on 27 January 2025, before advancing south to seize Bukavu, South Kivu’s capital on 17 February.

In a new offensive that began in December 2025 – just days after a US-brokered peace deal between Rwanda and the DRC was signed – M23 pushed farther south, capturing the city of Uvira on the border with Burundi.

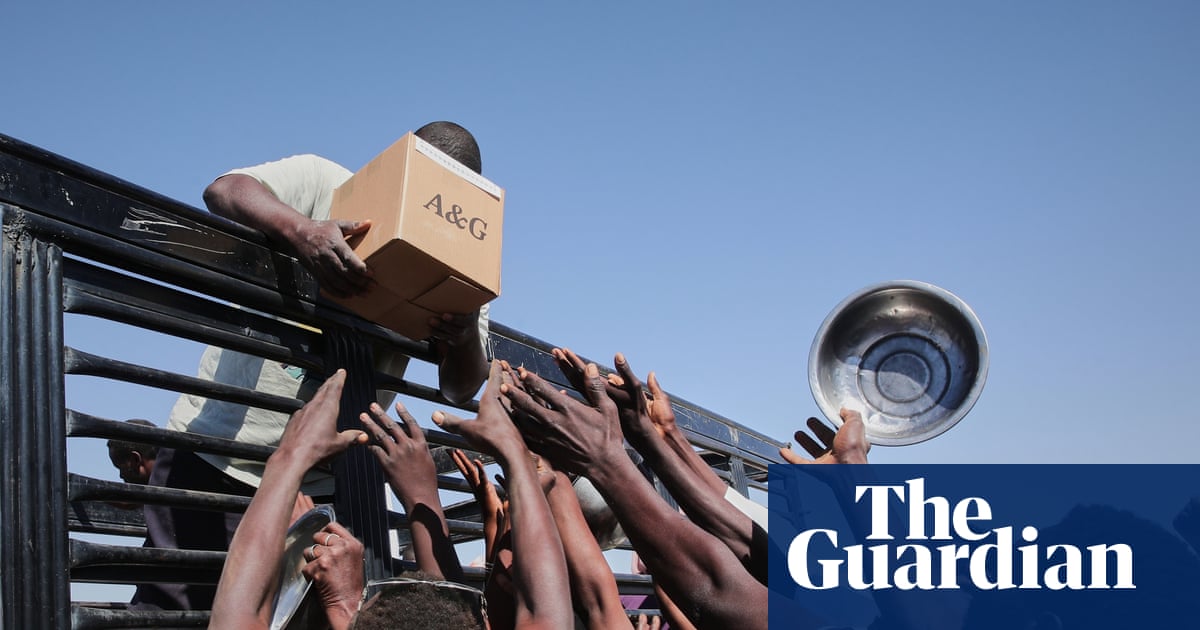

A Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) report from January estimates that nearly 65,000 refugees are living in Busuma refugee camp in Ruyigi, Burundi. A UNHCR report puts the total number of Congolese refugees seeking asylum in Burundi at about 200,000.

The scale of arrivals is “unprecedented”, says Aimable Hakizimana, field coordinator at the International Rescue Committee in Ruyigi. “The number [of refugees in Busuma] continues to rise, placing enormous pressure on existing services.”

“We were told on the phone that everything we left behind had been stolen or looted,” Muka says. Their journey from Luvungi began on 5 December. His wife, Noella Zawadi, was eight months pregnant and caring for two toddlers.

“It was better that I made sure my wife and children were safe, even if that meant losing everything else.”

The gruelling walk was only the beginning. “It was very difficult for me,” says Zawadi, “because I was late into pregnancy, I was looking after the two little ones and I was carrying some things. But I pushed through it.

“For the kids it was worse. They were hungry, and sometimes they saw dead bodies. That was very shocking for them.”

Before fleeing Luvungi, the family had lived a relatively stable life. Like many in the region, Muka farmed his own land and had planned to sell two tonnes of maize he had harvested. He also owned livestock that included nine cows and four goats.

By 7 December, they had reached the town of Sange, 30km south of Luvungi. Then it too was bombed, forcing the family to flee again. Eventually, they crossed into Burundi. Only then did the full weight of what they had lost begin to sink in. “As soon as the fighting began, I left without my cows. We raised them, and we used to milk them but, you know, that’s war,” Muka says. “I had a motorcycle too, to get around. That was lost, too.”

Faced with hunger, especially that of the children, Muka made a painful decision about the livestock he had managed to bring. “We sold some [of our goats] to get cash. Some died on the way. Those that died we ate because it was the only thing we had.”

Zawadi mourns the smaller things that once brought her children joy. “Back in Luvungi my son had a little bicycle we managed to buy for him. He loved it and rode around on it quite a lot. He was happy doing it.”

Items that once held the family together, preserving memories, were stolen or lost. “We had a pretty large collection of family photos that we used to keep, they were very important to us,” Zawadi says. “We had a lot of clothes that we used to wear when we went to church together every Sunday, we left some behind, and some others were lost on the way.

“It’s the clothes for the children that saddens me the most, those I know for sure I’ll never be able to get back. I even had some blankets I used to cover them with; those were lost, too.”

When Zawadi gave birth to her third child, she received new blankets from Healthnet TPO, but those were stolen soon after their arrival in Busuma. “It gets cold at night,” she says in a voice memo. “I don’t have anything to cover my baby with now.”

Hakizimana later explains that Zawadi had been difficult to reach because the newborn had fallen ill.

On 19 January, M23 announced it had withdrawn from Uvira. Still, Muka has no intention of returning home. “There is absolutely no desire to go back,” he says. “I have grieved for the people and things I lost. I’m not going back.”

But Busuma is not a long-term solution either. Health risks remain high, and infrastructure is stretched thin. “Resources are far below what is needed to meet basic needs,” Hakizimana says. “There is also a significant risk of disease outbreaks due to overcrowding.”

For Muka, there is one small consolation. “I have my family,” he says, as his children play in the background. “We only have two sets of clothes for them we managed to keep, and some cash left from selling the goats.”

Still, pangs of homesickness linger. “Everything I have reminds me of home,” Muka says. “It reminds us of everything we lost.”

3 hours ago

5

3 hours ago

5