On a Wednesday evening in September, about 6,000 people cross footbridges to reach Brown’s Island, a bucolic park in the middle of the James River in Richmond, Virginia. They’re here to see Turnstile, the Baltimore band who came from the hardcore punk underground but whose reach expands far outside that world.

Turnstile take the stage to a shimmering swell of keyboards – the intro from Never Enough, the title track from their new album. It’s a slow song by Turnstile standards, a tender confession of self-doubt that builds into a cathartic singalong. The moment that the song ends, Turnstile jump directly into TLC (Turnstile Love Connection), a frantic fist-pumper from 2021’s Glow On, and the crowd become a mass of flailing limbs. For the next hour-plus, bodies fly in all directions, as strangers scream lyrics into each other’s faces. Every new riff, every change in tempo, brings a fresh wave of sweaty euphoria.

Turnstile gigs have been like this for years. In the early days, the band played dive bars and church halls, and the shows never took place entirely on stage. Frontman Brendan Yates would dive balletically into the crowd, and the stage would be a constant blur of people from the audience running up, grabbing the microphone to belt out a line or two and then leaping back off.

In 2009, a teenage Yates dropped out of college to become the drummer for the mythically tough Baltimore hardcore band Trapped Under Ice. He formed Turnstile with close friends a year later, and the band had a tremendous underground buzz from the very beginning. By the time they released their full-length debut Nonstop Feeling in 2015, they were one of the biggest bands in hardcore. Where many of their peers went for heavy extremity, Turnstile’s dizzy hooks and colourful aesthetics set them apart. Before long, they started to attract fans far outside their subculture.

When I saw my first Turnstile show at a Washington DC church hall in 2018, drummer Daniel Fang played in a hospital gown. He’d missed one Turnstile show because he’d injured himself while training for the tour. Fang tells the story as the band checks in on a Zoom call from a Mesa, Arizona hotel room a few weeks after the Richmond show. “The doctor was like: ‘You will have kidney failure if you go play the show. Don’t do that,’” Fang recalls. But he refused to miss the show, so he checked out of the hospital and drove himself. “I was delirious in pain, but then felt the kind of amplified beauty of it, too. It was so, so joyous.”

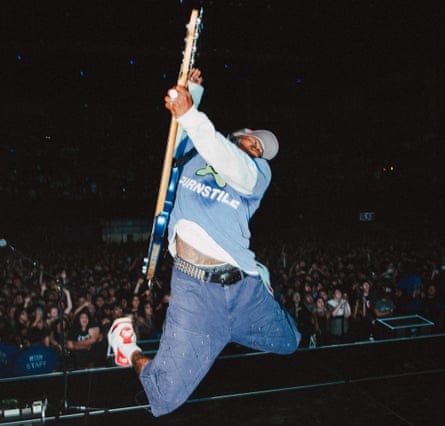

The joy was what really struck me – not just the dedication it must have taken for Fang to check himself out of the hospital, but the rapture that Fang and his bandmates all clearly felt that night. It was one of the greatest performances I’ve ever witnessed. An image has lived in my head ever since: Yates jumping off the stage during the first song and seemingly hanging in the air for hours before completing a full flip and landing in the crowd. Gigs like that turned fans into evangelists, and the band’s momentum kept growing.

Turnstile’s third album, 2021’s Glow On, was the breakout moment. For that album, the band worked with veteran pop producer Mike Elizondo and moved toward a sunnier sound, with shimmering hooks and percussive breakdowns, that was still rooted in hardcore catharsis. The record arrived just as Covid lockdowns ended, and its charged energy was infectious. Turnstile’s audience grew exponentially. They got Grammy nominations, toured arenas with Blink-182 and served as the sole rock band at rap festivals such as Rolling Loud in Miami.

Earlier this year, just before the release of Never Enough, many thousands of people came to Turnstile’s free daytime show at Wyman Park Dell in their home town. Every moment was marked by friends and well-wishers rushing the stage, only to cartwheel or backflip right back off. These days, however, every Turnstile set can’t be like that. The crowds that come to see them are simply too big. They need to play venues with barriers between them and the fans, so they find ways to convey all that frenzied energy on their own. They always figure it out.

Much of the magic of a hardcore show is in the lack of distinction between performers and crowd – the way the audience themselves become the show. When Turnstile play to thousands every night, they can’t recreate the feeling in the same way, but they find other ways to channel and direct that collective energy. “The biggest transition was learning how to make the show happen on the stage instead of us just being a part of the show,” says bassist Franz Lyons. “You start learning that you need to create the energy with all five of you, to just band together and display that right on the other side.”

Onstage, the five members of Turnstile are always in motion: jumping, spinning, stomping, calling for the crowd to give them more. They sweat buckets, with dazed and victorious looks in their eyes. It’s exhausting just to watch, but when you’re near the front at a Turnstile show, you can’t really watch. You’re too busy careening around and crashing into people yourself.

You don’t see a lot of upraised phones at Turnstile shows. People need to be alert. In the old days, someone could always jump offstage and land on your head. Even with the barriers preventing stagedives, a Turnstile gig is still a full-body immersion experience. But it’s welcoming, not forbidding. The giant screen at the back of the stage doesn’t often display what happens onstage. Instead, it shows the giddy, ecstatic faces of the people in the crowd: people of different backgrounds, races, ages and genders, all caught up in the moment.

That utopian vision can’t always be maintained. Turnstile end the Richmond show with Birds, a community-minded rager from Never Enough: “Finally, I can see it! These birds not meant to fly alone!” During the breakdown, Yates demands: “Get up here!” People finally scramble over the barrier, joining the band on stage. But amid the rush of bodies, a sheriff’s deputy sprays one fan, a teenage boy, with a stream of pepper spray to the face in what appears to be a completely unwarranted display of force. Fumes from the spray visibly affect Lyons, who stops playing his bass and covers his face. Video of that moment goes viral. In the days that follow, Richmond’s sheriff claims that the incident is under internal investigation while refusing to answer reporters’ questions about it.

Yates still sounds upset when he reflects on the way the Richmond show ended. “A cowardly action from an officer coming in and spraying a 15-year-old kid and then walking away – I don’t think that’s an isolated event,” he says. “But at our shows, it was a new thing. It’s something that we strive to keep away.”

after newsletter promotion

When you’re playing aggressive music for vast, fired-up crowds every night, a certain amount of chaos is unavoidable. “You can’t really control things like that when they happen,” says Yates. “But I think we do our best to always be very eyes open for things. Sometimes, it’s the nature of big events and people coming together.”

At this point, every Turnstile show is a big event. Their North American tour is a labour of love. They have sought out venues without seats, sometimes developing whole new venues when those spaces don’t exist in those cities. “The Denver show was just a stage under a bridge, and it was the first time they’d done a show there,” says Yates. “In LA, we just built a stage in a big park.” The band carefully curated the tour lineup, which covers a wide spectrum. The glitchy pop experimenter Jane Remover and the swaggering Australian heavy hardcore band Speed are on board for the entire run, with groups such as Melbourne’s Amyl and the Sniffers and Philadelphia’s Mannequin Pussy jumping aboard at different points. In November, the band will take a version of the tour to the UK and Europe, with heart-on-sleeve London rockers High Vis and experimental California thrashers the Garden opening.

Yates says that Turnstile always seek out tourmates that share “a connected thread” with the band: “Sometimes, it’s sonic threads. Sometimes, it’s an ethos thread, or something that’s sonically exciting that pairs together and creates something that feels like it could be really interesting. It gives everyone an opportunity to come and bring different people out and experience new things – but not in a random way, in a very intentional way.”

That intentionality extends to Turnstile’s music. It’s still rooted in that explosive catharsis of hardcore, but lots of other sounds shine through: dance music, synthpop, funk. Never Enough has flute from London jazz great Shabaka Hutchings, vocals from Paramore’s Hayley Williams and singer-songwriter Faye Webster, and production from Charli xcx collaborator AG Cook. One highlight is Look Out for Me, an expansive, seven-minute odyssey that veers from crisp, mosh-ready riffage into the homegrown house subgenre known as Baltimore club music. Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes contributed to the last two Turnstile albums. At the Richmond show, Hynes plays an opening set and gets a roar from the crowd when he joins Turnstile for Alien Love Call, his 2021 duet with Yates.

Even as Turnstile venture further afield from the hardcore underground that birthed them, their live shows still stand as expressions of community. It’s not easy to maintain that feeling when you’re playing to thousands every night, but Turnstile remain rooted in the city and the scene where they started. Other than new guitarist Meg Mills, a veteran of UK punk bands like Big Cheese and Chubby and the Gang, all of them still live in Baltimore. Yates still plays drums for his old band Trapped Under Ice whenever he gets the chance, and Lyons often joins them on stage.

Lyons’ bandmates marvel that Lyons is “in the mix all the time”, that he’ll still have the energy to hit a local punk show right after returning from a tour. “These are the things that I actually love to do, just like everybody else [in the band] loves to do,” says Lyons. “The passion for that, it doesn’t stop at being in our band.”

That passion extends outward. It’s infectious. “I’m continuously seeing them do new things that I’ve never seen,” says Trapped Under Ice and Angel Du$t frontman Justice Tripp, a big-brother figure to the members of Turnstile, calling in from his tour van. “I’ve seen every young band from Baltimore brainstorming what they can do to have an impact like that. It causes waves. It causes people to step outside what they know and redesign what it means to be an artist and contributing to our culture or your city.”

Yates insists that Turnstile don’t have a gameplan: “We try to maintain a level of appreciation for the present. Focusing too far ahead doesn’t really do much for you.” It makes sense. Nobody could’ve plotted Turnstile’s rise from church halls to festival stages. It’s the kind of thing that can only happen through sweat, dedication and an absolute belief in what they’re doing.

When Turnstile members talk about playing live, they sometimes speak in almost mystical terms. Lyons says: “It’s been years in the making – learning how to really work on that chemistry and togetherness, making the energy onstage so much that it can touch the people who are on the other side.”

Turnstile tour the UK and Ireland from 1 to 5 November; tour starts Dublin. Never Enough is out now.

2 months ago

52

2 months ago

52