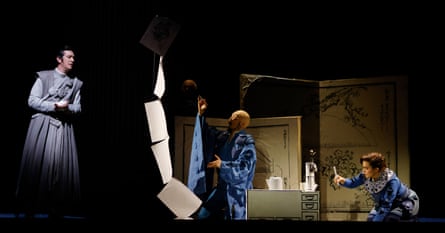

‘I might become the art myself,” sings the artist Katsushika Hokusai in the new opera by composer Dai Fujikura and librettist Harry Ross. And here he is, doing just that: played by the baritone Daisuke Ohyama, with the forces of Scottish Opera ranged around him.

Over five acts, The Great Wave gives us episodes from Hokusai’s life and death, beginning with his funeral then continuing in flashback, including a dream sequence in which he encounters the wave that inspired his most famous print. As you might expect, it looks beautiful. The production is the work of an all-Japanese team headed by the director Satoshi Miyagi, and it’s full of Hokusai’s pictures, projected upon the bamboo walls of Junpei Kiz’s set, which reflect the artist’s barrel-shaped coffin. It often sounds beautiful, too: Fujikura uses the shakuhachi – a recorder-like flute, played by Shozan Hasegawa – as the basis for a light-infused soundworld conjuring openness and simplicity in almost Copland-esque style, made piquant with fluttering, elusive orchestral textures.

Everyone begins wearing white – blank canvases – but Hokusai and Ōi, his daughter and helpmeet, gradually become soaked in the expensive Prussian blue pigment that, this being closed-off 19th-century Japan, must be obtained through forbidden trade with the dreaded Dutch. There’s no real jeopardy, though: we learn in passing that Hokusai’s house has burned down, and that he risks execution for trading with the Dutch, but none of these things trouble him. Even when a bunch of elegantly dancing heavies are poised to lop off the toes of his grandson, who has run up gambling debts, he goes on painting.

So it’s less the retelling of a life story, more a series of extended vignettes, or a Philip Glass-style meditation. But on what? There’s a reason why there are so few successful stage works about successful artists. Hokusai is a happy man whose only wish is for a long life so that he can continue to develop his art. At more than one point – for example, when Hokusai is dashing off glorious animal pictures for a queue of fans – it feels like a discussion of the mechanics of giving the public what they want. As for Ōi, she’s an artist herself, a divorcee who has returned to her father’s house as his assistant – but if her feelings about this are even remotely mixed, we barely hear of it.

Vocally, Ōi is the star, and Julieth Lozano Rolong radiates her generous nature, singing in a glowing high soprano. There are strong performances, too, from the supporting cast, including Shengzhi Ren, doubling as Hokusai’s canny agent and a sweetshop owner wistfully remembering his favourite customer, and the sweet-sounding tenor Luvo Maranti as the pesky grandson. Conducted by Stuart Stratford, the orchestra and chorus play and sing with absolute conviction.

Cash-strapped Scottish Opera has been able to develop a project with funding attached and has run with it admirably. With an exhibition in the foyer and a programme book full of interesting essays, there’s a lot to be learned about Hokusai here. But don’t expect the opera to do the job on its own.

7 hours ago

6

7 hours ago

6