Naseem Hamed carries himself with a stately grandeur these days. Having settled his considerable bulk into a comfortable chair he pauses meaningfully. We look at each other intently and it’s hard to believe the incorrigible little “Naz fella”, the swaggering Prince Naseem who became a world champion 30 years ago and changed British boxing forever with his dazzling aptitude for fighting and showmanship, is 51 now.

“This is the one thing you need to understand,” Hamed says as he remembers Brendan Ingle’s famous old gym in Sheffield. “The minute I walked through the doors of that boxing club, that was it. I saw the ring, the bags, the lines on the floor, and I was immediately obsessed. This was going to be my life. I saw boxing as a game of tag. I’m going to hit you and you can’t hit me. It took speed and accuracy and I was really good at it.”

I first saw Hamed box in April 1992, when he knocked out Shaun Norman in two rounds on a Chris Eubank bill in Manchester. He was a Bambi-faced 18-year-old whose strutting exuberance belonged to a junior Strictly Come Dancing extravaganza. I could imagine a husky ballroom cry: “Representing Sheffield and Yorkshire in the salsa, it’s the young Prince …”

Two years later, in May 1994, he became the European bantamweight champion in only his 12th professional fight when he humiliated Vincenzo Belcastro. The Italian had never been knocked down before but Hamed dropped Belcastro with his first punches – a gorgeous right–left combination that dumped the champion in a heap.

The Prince could have ended the fight at any time but he stretched out the massacre over 12 rounds to showcase his brilliance and cruelty. At one point he stared at poor Belcastro’s feet while thudding punches into his face. After flooring his victim again in the 11th, Hamed spat out more needless taunts and mesmerising combinations.

Hugh McIlvanney, the great boxing writer, led the condemnation. Describing the Prince as “a spectacular talent … his effortless mastery of Belcastro, a seasoned pro, was an astonishing feat”, McIlvanney also deplored Hamed’s “eagerness to treat his demoralised victim as he were something no better than what you would wipe off your shoe”.

Hamed’s remarkable boxing skills and complicated persona had been honed by Ingle who began working with him when Naz was only seven years old. Ingle promised he would become one of the greatest boxers in history and Hamed believed his Irish trainer with utter certainty. “I was this little frail kid that didn’t look like I could punch myself out of a paper bag. But I honestly believed I could change the sport. And I did.”

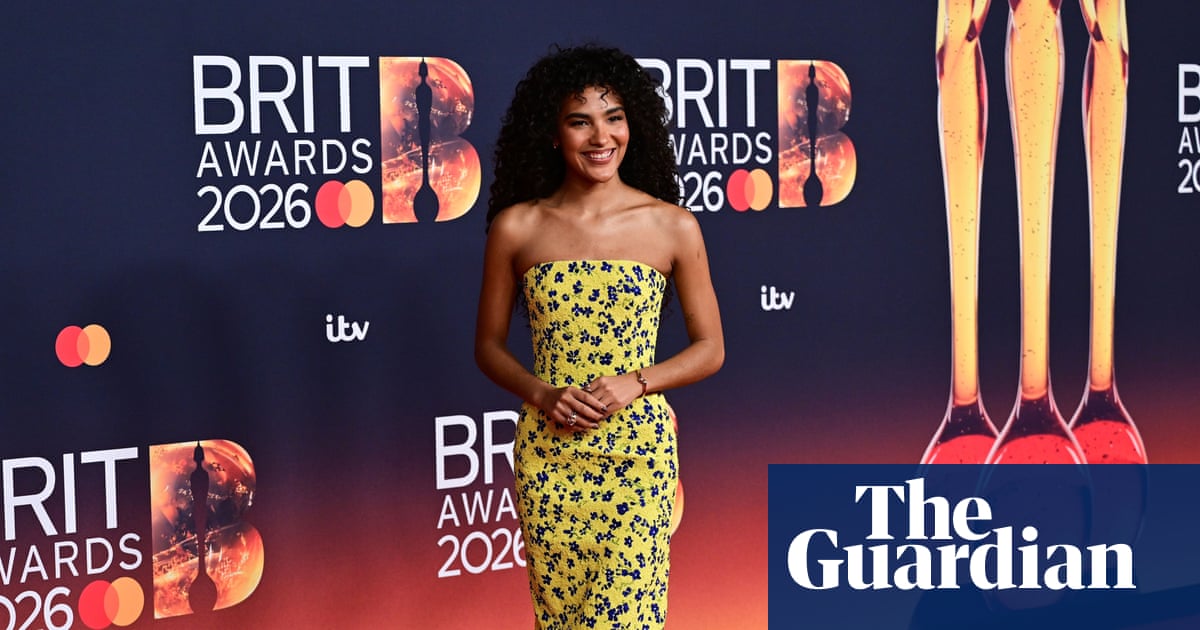

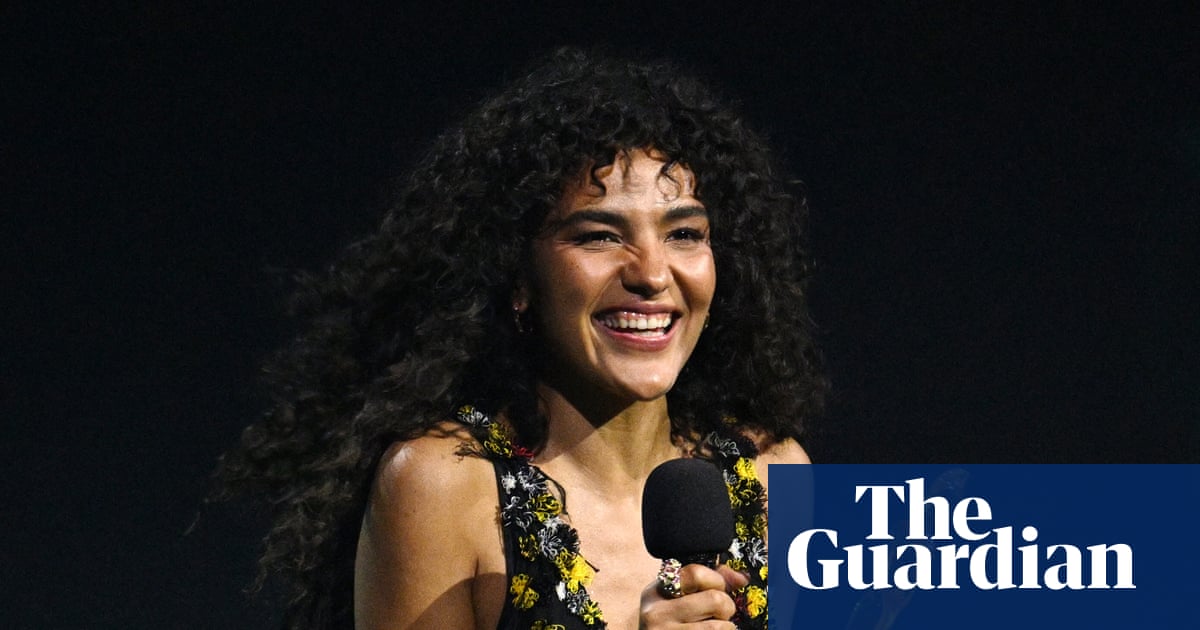

A new film, Giant, starring Amir El-Masry as Hamed and Pierce Brosnan as Ingle, opened in British cinemas on Friday. It concentrates on the tangled relationship between Hamed and Ingle and the way in which money and fame unearthed previously hidden resentment. Hamed has helped publicise the film but he tells me he watched it with “mixed emotions”.

His rise was packed with cultural significance. Hamed was the first leading British fighter who was neither black nor white, resulting in racial taunts and misguided descriptions of him as the country’s “only professional Asian boxer”. He called himself a British and an Arab fighter, a Yorkshireman of pure Yemeni stock. When I first interviewed him in 1994 the 20-year-old said: “I am a Muslim, from Yemen, but born and bred in Sheffield. That tells you everything you need to understand about me.”

In Yorkshire in the early 1980s, when the National Front was active, it did not pay to be a little Arab boy. Ingle had often spun the story of how he first laid eyes on Naz – a tiny figure fighting off three much bigger white boys. “I was on this double-decker bus,” Ingle recalled, “and we came to a halt outside the primary school. There’s thuggery goin’ on but the smallest lad, the boy I took to be Asian, is punching beautifully, hitting all three of them. They can’t land a shot on him. I said to myself: ‘That young fella can fight.’”

Hamed nods when I mention the National Front slogans seen in Giant. “It was all over the walls near the gym, not far from my house. But the biggest problem wasn’t just racism. The [boxing authorities] absolutely hated Brendan because he was Irish and producing fighters that were fighting different to everybody else in the country. We were hitting them and then moving.

“If it wasn’t for Brendan, how would I have been able to get really good? How would I have been able to learn the fundamentals of boxing, the footwork and confidence ingrained by him? And from the get-go it’s like the world was against us. All the amateur officials made it harder for us but the minute I became 18 I’d won enough cups and medals.

“I wanted to earn money for me and my family. I’m the son of an immigrant shopkeeper that came from Yemen. We don’t have any wealth in our family tree. So one of my greatest achievements was to make a new life for my parents, my brothers and sisters and my cousins.”

He and Ingle stopped working together at the peak of Hamed’s career when they were full of rancour and bitterness towards each other. Ingle died in May 2018, aged 77, having never spoken again to his most cherished boxer, and Hamed wants to make amends now. But he also wants to underline his own truth.

“I never saw Brendan as a father figure, even though he was trying to tell people he was like a father to me. I had my own father and I never lived in Brendan’s house – as they mentioned in the film. He did ask me to move into his home with his wife and kids but I refused because I lived just up the road with my eight brothers and sisters and my parents. I’m not going to jump ship from my own family. So a few moments are really sad between us.”

In December 1997, Hamed stopped Kevin Kelley in a tumultuous world featherweight title fight at Madison Square Garden in New York. It was the greatest night of Hamed’s career – even though he was knocked down three times by Kelley – and the film suggests that in the buildup the boxer had tried to kick Ingle out of his corner and not pay his trainer’s purse.

Hamed offers a different version: “Nobody actually knows this. But imagine [Ingle] coming to me before the biggest fight of my life, and saying: ‘I want you to leave the gym.’ It was before training camp had started and I’ve got the hardest fight of my whole career. Kelley was a world champion when I was still a kid. I was also in his back yard.

“But I refused to leave the gym. It was such a bad thing to say that to me but Brendan never really trained me. His son, John, trained me. John spent time with me in that ring, on the pads, to make sure that I got them punches so accurate. This has never been spoken about.

“I said to Brendan: ‘Your son is my trainer. He’s the one that went into my corner as an amateur for 67 fights. He’s the one I’m comfortable with.’”

The division with Brendan is back but Hamed catches himself: “Regardless, I always give him the credit of laying down them foundations. I always remember that … but in boxing these [enmities] can happen.”

He adds: “The whole world can think whatever they want about me. It’s never going to affect me. I’m not one to think: ‘Oh, this film makes me look so bad and I shouldn’t support it.’ No. It’s amazing they’re making a film about you.”

Giant offers two endings – with one imagining a happy reunion between the trainer and fighter. “It’s make-believe,” Hamed confirms but, in reality, he tried to forge a reconciliation with Ingle “many times. I reached out in so many different ways to make up with Brendan. I tried to sit down with him and apologise and ask him to forgive me. At the same time, I would have liked him to do the same, because it wasn’t one-way traffic. I felt we needed that but he was so stubborn. I was getting more mature and realising that, if you fall out with somebody, let’s make peace. We spent 18 years together.”

Hamed won his next six bouts after the Kelley fight, and his parting from Ingle, but he suffered his solitary defeat when he was humbled by the magnificent Marco Antonio Barrera in Las Vegas in April 2001. He fought only once more, against the obscure Manuel Calvo, 13 months later.

Nearly 25 years later, he lists a string of reasons why he was so disappointing against Barrera – including a broken hand, another change of trainer and a savage weight-cut. Hamed does not sound haunted by the loss and, typically of a proud old fighter, says: “When the final bell rang I was still on my feet. Mike Tyson, Sugar Ray Leonard, Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Robinson, the greatest fighters that ever lived, have been exposed, looking up at the stars. That never happened to me and that’s why that loss for me didn’t really feel like a loss.”

Hamed never fulfilled the grandest ambitions he and Ingle created but his good humour and health today is testament to his wisdom in retiring at 28. “People said: ‘Why would you stop so young?’ But I’d spent 10 years as a professional and 11 years as an amateur. Twenty-one years was enough. It will never be forgotten – not just in achievements but for young kids coming through seeing it as an inspiration. I had nothing else to prove.

“I’d won five world title belts and then the Hall of Fame came and it’s just amazing all these things happened to a young kid with big dreams.”

Hamed had also witnessed enough savagery in boxing. “We were taught by Brendan how dangerous the sport was,” he says. “There were boards up in the gym that said ‘Boxing can damage your health.’ When you was as good as I was, and you avoided getting hit, it was different. But I chose my time to get out. I could have stayed and done whatever I wanted in the sport. But our philosophy was to hit and not get hit.”

Does he wish he could change anything he did in or out of the ring? After a long pause Hamed says: “The biggest regret of my life …”

He catches me leaning forward and says, with his old teasing twinkle: “You’re so intrigued.”

I admit he’s right while wondering if Hamed might say anything more about Ingle, or taunting some of his rivals. He leans back in his chair and smiles. “This is so far from what you’re thinking but I’ve been brought up with a beautiful religion.

“So my biggest regret is that, when I was younger, I didn’t always do my five prayers [a day]. But I do now and it’s so important because the person I am today is the person I’ve always wanted to be.”

1 month ago

87

1 month ago

87