“He has been here and fired a gun,” John Constable said of JMW Turner. A shootout between these two titans would make a good scene for in a film of their lives, but in reality all Turner did at the 1832 Royal Academy exhibition was add a splash of red to a seascape, to distract from the Constable canvas beside it.

That was by far the most heated moment in what seems to us a struggle on land and sea for supremacy in British art. It’s impossible not to see Tate Britain’s new double header of their work this way. For it is a truth universally acknowledged, to paraphrase their contemporary Jane Austen, that when two great artists live at the same time, they must be bitter and remorseless rivals. But is that really so, and does it help or hinder creativity?

The Renaissance sculptor Benvenuto Cellini literally fired guns, blasting a man to death at close range with an arquebus. But when he contemplated murdering his rival Baccio Bandinelli, whom he claimed was “full of badness” and whose statue of Hercules looked “like a sack of melons”, it was with his trusty dagger. Cellini spotted Bandinelli across a quiet piazza, according to his autobiography, and reached for his blade to end their competition for Medici patronage with a single knife blow – but spared him.

It’s just one intense moment recorded between Renaissance artists. In fact the story of the Renaissance can be told as a series of rivalries: Cimabue v Giotto, Bellini v Giorgione, Michelangelo v Raphael, Michelangelo v Bramante, Michelangelo v Titian and of course Michelangelo v Leonardo da Vinci. Michelangelo, the feuder’s feuder, humiliated Leonardo by telling him in front of others he was a failure: “You who promised to make a bronze horse in Milan and couldn’t do it.” Leonardo got his revenge when he called for Michelangelo’s David to be made “decent” with bronze underpants.

When Artemisia Gentileschi moved to Naples, she had to get a weapons licence in a city so tough it had an art mafia known as the Cabal that violently menaced rivals. In 1621 the Cabal, led by the painter Jusepe de Ribera, severely wounded the visiting artist Guido Reni’s assistant to scare him out of Naples. It may also have lethally poisoned Domenichino, another outsider who got a big commission.

You can’t really call that healthy competition. But it was believed in Renaissance Italy that rivalry was constructive, with artists driving one another on: given the works it produced, the theory may have something in it. Michelangelo’s most creative standoff was with Titian. He once said the Venetian painter would be really good, if only he could draw. Despite this catty remark, the two artists mutually influenced each other, Titian borrowing the pose of Michelangelo’s statue Night for his nude painting Danaë, Michelangelo rivalling Titian’s colour and space in his The Last Judgment.

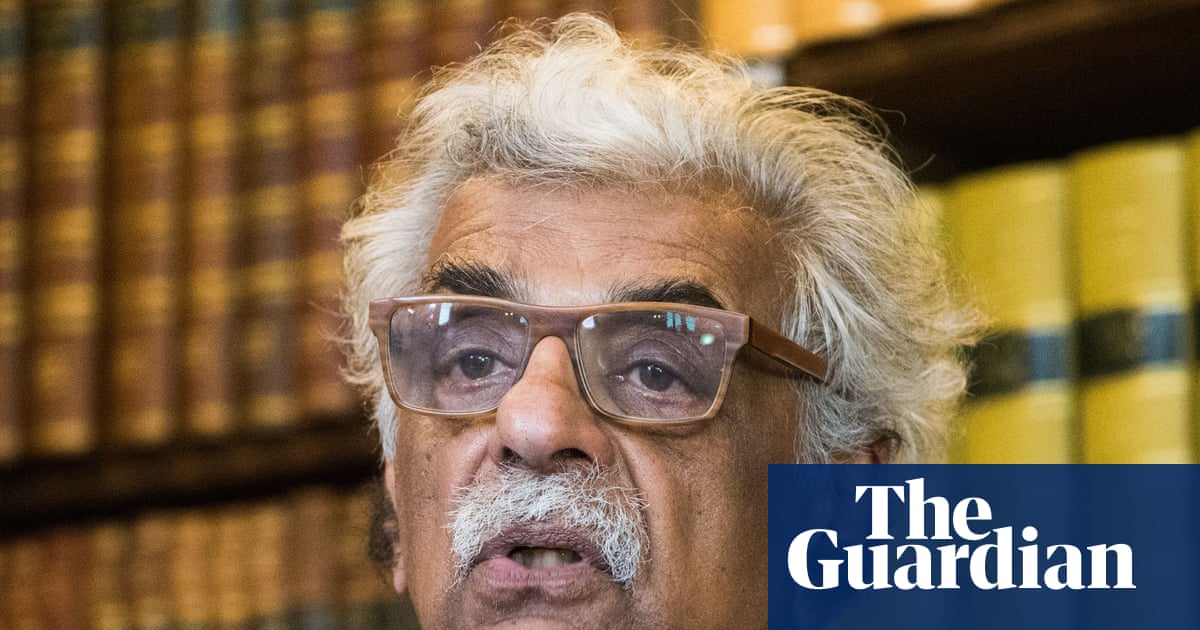

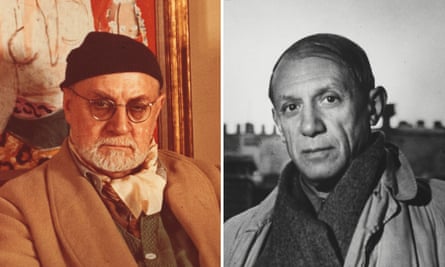

Such epic rivalries have happened in modern times. After Francis Bacon died in 1992, Lucian Freud bloomed, painting his colossal, heroic nudes of Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley. They were friends, and on Bacon’s part it may have been love, but there was some sense in which Bacon’s brilliance daunted the younger man. With Picasso and Matisse it was the opposite: after Matisse died, Picasso’s art went flabby. They’d pushed and pulled each other in rivalry for decades, ever since Matisse gave Picasso a painting in 1907 and Picasso, it was gossiped, used it as a dartboard.

Yet such grand creative tensions went against the opposite tendency for modern artists to bond together. Were there undercurrents of rivalry between Monet and Renoir, Dalí and Magritte, Pollock and De Kooning? Maybe, but avant gardes from the Impressionists onwards saw themselves as gangs of friends united against the bourgeois enemy. When Gauguin and Van Gogh fell out it wasn’t because of rivalry, but Vincent’s illness. Picasso, while rivals with Matisse, collaborated harmoniously with Braque to create cubism.

This belief that artists should be collaborators rather than rivalrous enemies is very much in fashion. The 2019 Turner Prize nominees even chose to share the award as a “collective”. It was charming, but what would Turner have said, let alone Michelangelo? Shunning competition makes the Turner Prize feel pointless. It may be why there are no more art heroes any more.

Artistic competition goes to the essence of critical discrimination. TS Eliot said someone who liked all poetry would be very dull to talk to about poetry. Double header exhibitions that rake up old rivalries are not shallow, but help us all be critics and understand that loving means choosing. If you come out of Turner and Constable admiring both artists equally, you probably haven’t truly felt either. And if you prefer Constable, it’s pistols at dawn.

2 months ago

63

2 months ago

63