Five years ago, on the verge of the first Covid lockdown, I wrote an article asking what seemed to be an extremely niche question: why do some people invert their controls when playing 3D games? A majority of players push down on the controller to make their onscreen character look down, and up to make them look up. But there is a sizeable minority who do the opposite, controlling their avatars like a pilot controls a plane, pulling back to go up. For most modern games, this requires going into the settings and reconfiguring the default controls. Why do they still persist?

I thought a few hardcore gamers would be interested in the question. Instead, more than one million people read the article, and the ensuing debate caught the attention of Dr Jennifer Corbett (quoted in the original piece) and Dr Jaap Munneke, then based at the Visual Perception and Attention Lab at Brunel University London.

At the time, the two were conducting research into vision science and cognitive neuroscience, but when the country locked down, they were no longer able to test volunteers in their laboratory. The question of controller inversion provided the perfect opportunity to study the neuroscience of human-computer interactions using remote subjects. They put out a call for gamers willing to help research the reasons behind controller inversion and received many hundreds of replies.

And it wasn’t just gamers who were interested. “Machinists, equipment operators, pilots, designers, surgeons – people from so many different backgrounds reached out,” says Corbett. “Because there were so many different answers, we realised we had a lot of scientific literature to review to design the best possible study. Readers’ responses turned this study into the first of its kind to try to figure out what actually are those factors that shape how users configure their controllers. Personal experiences, favourite games, different genres, age, consoles, which way you scroll with a mouse … all of these things could potentially be involved.”

This month the duo published their findings in a paper entitled “Why axis inversion? Optimising interactions between users, interfaces, and visual displays in 3D environments”. And the reason why some people invert their controls? It’s complicated.

The process started with participants completing a survey about their backgrounds and gaming experiences. “Many people told us that playing a flight simulator, using a certain type of console, or the first game they played were the reasons they preferred to invert or not,” says Corbett. “Many also said they switched preferences over time. We added a whole new section to the study based on all this feedback.”

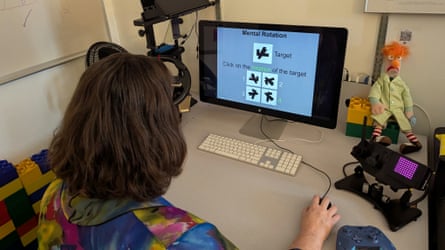

But Corbett and Munneke, now based at MIT and Northeastern University respectively, were certain that there would also be important cognitive components to the inversion question that could be measured only through behavioural responses. So they devised a questionnaire and a series of four experiments that participants would take part in while being instructed and observed via Zoom. As Corbett explains: “They had to mentally rotate random shapes, take on the perspective of an ‘avatar’ object in a picture, determine which way something was tilted in differently tilted backgrounds, and overcome the typical ‘Simon effect’ where it’s harder to respond when a target is on the opposite v the same side of the screen as the response button. Then we used some machine-learning algorithms to help us sort through all this survey and experiment data and pick out what combination of all of these things best explained whether someone inverted.”

What they discovered through the cognitive testing was that a lot of assumptions being made around controller preferences were wrong. “None of the reasons people gave us [for inverting controls] had anything to do with whether they actually inverted,” says Corbett. “It turns out the most predictive out of all the factors we measured was how quickly gamers could mentally rotate things and overcome the Simon effect. The faster they were, the less likely they were to invert. People who said they sometimes inverted were by far the slowest on these tasks.” So does this mean non-inverters are better games? No, says Corbett. “Though they tended to be faster, they didn’t get the correct answer more than non-inverters who were actually slightly more accurate.”

In short, gamers think they are an inverter or a non-inverter because of how they were first exposed to game controls. Someone who played a lot of flight sims in the 1980s may have unconsciously taught themselves to invert and now they consider that their innate preference; alternatively a gamer who grew up in the 2000s, when non-inverted controls became prevalent may think they are naturally a non-inverter. However, cognitive tests suggest otherwise. It’s much more likely that you invert or don’t invert due to how your brain perceives objects in 3D space.

Consequently, Corbett says that it may improve you as a gamer to try the controller setup you are currently not using. “Non-inverters should give inversion a try – and inverters should give non-inversion another shot,” she says. “You might even want to force yourself to stick with it for a few hours. People have learned one way. That doesn’t mean they won’t learn another way even better. A good example is being left-handed. Until the mid-20th century, left-handed children were forced to write with their right hand, causing some people to have lifelong handwriting difficulties and learning problems. Many older adults still don’t realise they’re naturally left-handed and could write/draw much better if they switched back.”

Through this research, Corbett and Munneke have established that there are complex and often unconscious cognitive processes involved in how individuals use controllers, and that these may have important ramifications for not just game hardware but for any human-computer interfaces, from aircraft controls to surgical devices. They were able to design a framework for assessing how to best configure controls for any given individual and have now made that available via their research paper.

“This work opened our eyes to the huge potential that optimising inversion settings has for advancing human-machine teaming,” says Corbett. “So many technologies are pairing humans with AI and other machines to augment what we can do alone. Understanding how a given individual best performs with a certain setup (controller configuration, screen placement, whether they are trying to hit a target or avoid an obstacle) can allow for much smoother interactions between humans and machines in lots of scenarios from partnering with an AI player to defeat a boss, to preventing damage to delicate internal tissue while performing a complicated laparoscopic surgery.”

So what started as an idle, slightly nerdy question has now become a published cognitive research paper. One scientific publication has already cited it and interview requests are pouring in from podcasts and Youtubers. As for my takeaway? “The most surprising finding for gamers [who don’t invert] is that they might perform better if they practised with an inverted control scheme,” says Corbett. “Maybe not, but given our findings, it’s definitely worth a shot because it could dramatically improve competitive game play!”

3 months ago

103

3 months ago

103