Zipcar, the world’s largest carsharing club, is leaving the UK. The company, which operates about 3,000 shared vehicles in Britain, has announced plans to shutter its UK operations at the end of the month. The news comes as a bitter blow to the hundreds of thousands of Britons who regularly rely on carsharing, and is a major setback in efforts to reduce emissions and traffic congestion.

I’m particularly gutted. This year I finally learned to drive, specifically in order to become a Zipcar member for the rare occasions when I need a vehicle. As newly qualified drivers aren’t allowed to hire Zipcars until they’ve held a licence for a year, I bought a secondhand VW Beetle to tide me over, counting the days until I could flog it and sign up for Zipcar instead. Now, with the service shutting up shop, I fear I will be stuck maintaining a costly lump of steel that I need for less than 1% of the year.

Growth in private car ownership is a problem. Domestic transport remains the largest source of emissions in the UK. Expanding car clubs such as Zipcar could have helped, as research suggests each shared vehicle replaces about 20 private cars.

Yet Britain was already lagging behind our neighbours in car clubs. According to Invers, a carsharing tech company, Germany has more than six times as many shared cars per capita as Britain. Zipcar’s departure will reduce the total number of shared cars in the UK to just one for every 30,000 people – effectively eliminating carsharing for huge swathes of the population.

The impending collapse of UK carsharing should be a severe embarrassment to the government, which elsewhere is attempting to curb car dominance. The revised National Planning Policy Framework, for example, has an entire section dedicated to expanding sustainable transport, including carsharing, and a requirement for local authorities to “promote sustainable travel modes that limit future car use”. But what good is setting lofty policies for tomorrow without supporting the companies and services that can enable better choices today?

In last week’s budget, Rachel Reeves showered the private-car sector with funding, raising subsidies for new electric cars to £1.95bn and topping up grants for new electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure to £500m.

Reeves’ EV giveaway comes as she coughed up £1.5bn to underwrite a loan to Jaguar Land Rover after a recent cyber-attack, and froze fuel duty for yet another year. How is the chancellor finding billions to support the private car sector but offering nothing to support (massively more cost-effective) car clubs and their 328,539 users?

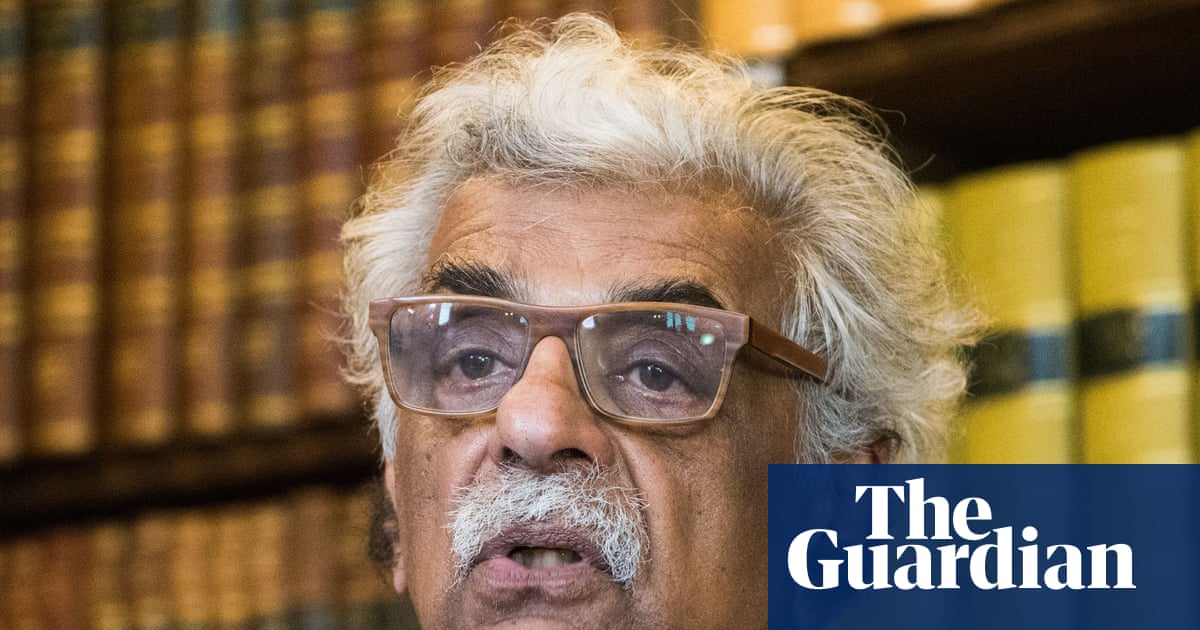

Arthur Kay, a Transport for London board member and author of the new book Roadkill: Unveiling the True Cost of Our Toxic Relationship with Cars, fears that the Treasury has been seduced by the claims of electric car manufacturers, and is funnelling money into questionable EV rollouts that could otherwise be supporting effective schemes supporting reduced and shared car-use schemes. “The EV lobby has so effectively captured the state,” he tells me, but warns that “changing the fuel source doesn’t change all the other things that are bad about cars”.

The truth is that electric cars are no panacea. They are quieter and spew fewer direct emissions than their petrol counterparts, but still produce brake, tyre and other particulates that account for a large portion of driving-based air pollution. EVs are also carbon-intensive to manufacture, and require energy from the grid to run most of the time; some EV cars only reduce the carbon emissions of driving by 47%.

Shockingly, rising private electric car ownership may also actually be fuelling more car use. In Norway 94% of new cars sold are now electric thanks to astronomical public subsidies. However, a little-reported study has revealed a hidden dark side to the Scandinavian EV revolution. In September, researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology found greater EV ownership is driving an overall increase in car trips of 10-20%. Just as building new roads increases traffic by encouraging more people to drive, so, too, flooding Norway with shiny new private EVs has prompted more Norwegians to get behind the wheel.

after newsletter promotion

EVs, though a clear improvement on their petrol predecessors, reproduce many of the same problems of car-based urbanism, binding us into a system of maintaining expensive machines that are stationary 95% of the time. The loss of Zipcar isn’t a business failure; it’s a warning that our leaders’ transport priorities are out of whack. Ultimately, if we want a country built for people rather than parked cars, we need to get serious about sharing.

-

Phineas Harper is a writer and curator

1 month ago

60

1 month ago

60