Excited chatter and the clattering of steel plates drown out the din of the monsoon rains: it is lunchtime in Laitsohpliah government school in the north-east Indian state of Meghalaya. The food has been cooked on-site and is free for everyone, part of India’s ambitious “midday meal” – PM Poshan – programme to incentivise school enrolment.

The scheme covers more than 1m state-run schools across the country, but the menu at Laitsohpliah is hyperlocal, thanks to a recent charity initiative in the state.

-

A lunch of rice, dal, potatoes with east Himalayan chives, cured dry fish and sohryngkham, a wild berry pickle

This lunchtime, apart from the staple rice and dal, there is a dish of potatoes with east Himalayan chives, cured dry fish and sohryngkham, a wild berry pickle.

Much of it has been sourced from local farmers, including parents of the pupils, while the rest has been grown in the school’s kitchen garden.

“Our students don’t like skipping meals any more,” says the headteacher, Nestar Kharmawphlang, who has taught at the school for 30 years.

Across the remote state of Meghalaya – originally part of Assam and home to the Khasi, Jaintia and Garo communities – fresh, locally sourced ingredients such as millet, fruit and wild greens are used to supplement the carbohydrate-heavy fare of rice, lentils and the occasional egg that dominate the programme’s menus.

The shift is courtesy of an initiative by the North East Society for Agroecology Support (Nesfas), which aims to make school lunches healthier, more sustainable and climate-resilient. Since 2022, Laitsohpliah has been one of 26 government-run schools in the state where lunches are transforming children’s appetites and energy levels through the use of locally grown and nutrient-rich ingredients.

-

The school’s headteacher, Nestar Kharmawphlang, in his kitchen garden

-

East Himalayan chives and cured fish add nutritional value to the children’s food

Experts say the model is promising because while the government scheme, launched in 1995, has aimed to provide free, nutritious meals to its poorest children, its impact has been limited by budget constraints and other challenges in a country where more than half of children under five are chronically malnourished and more than a third are stunted.

“The results would need more independent scrutiny,” says Reetika Khera, a development economist who teaches at Delhi’s Indian Institute of Technology. “But in principle, decentralisation initiatives like these can reduce costs, ensure fresher produce and better nutrition.”

The local government in Meghalaya has taken note too, inviting the charity to train more than 7,000 school cooks with the aim of diversifying menus using indigenous foods.

Back at the school in Laitsohpliah, the cook serves lunch through a window of the school’s cramped kitchen.

-

At another local school, rice is served with dal, tomato salad mixed with wild edible leaves, lemon slices, and a cauliflower and vegetable gravy

-

Iarap Bor Lang Khongsit waits for his lunch at the kitchen window; and Offiliana Syiemlieh shows off her food

In the queue with his friends, 10-year-old Iarap Bor Lang Khongsit says he “loves the food at school”, and his favourite dish is an omelette made with finely chopped fiddlehead ferns and turmeric.

Millet, once disliked by many of the children, is now baked in cakes or brewed into a thick tea; grated carrot salads have sesame seeds, salt, onion and nei lieh (perilla seeds); potato cheese balls are made with chives; and dal is enriched with local pulses such as rice beans, similar to mung beans.

But it is about more than just appetising meals. Schools organise regular outings to nearby forests to teach the children to identify edible fruit and vegetables from the wild.

-

A school lunch of rice, pumpkin dal with chayote gourd, dry fish, chutney, egg, wild fish mint and pineapple

Offiliana Syiemlieh, 14, says she first discovered wild edibles at school. “Now, sometimes, I bring jamyrdoh [fish mint] grown by my mother at home to contribute to the school meal.”

Kharmawphlang says one goal of the scheme is to restore the relevance of traditional foods to everyday diets. “Jarain – our version of buckwheat – is rich in micronutrients, climate-resilient and able to withstand extreme temperatures,” he says. “Yet it was considered as feed for pigs.”

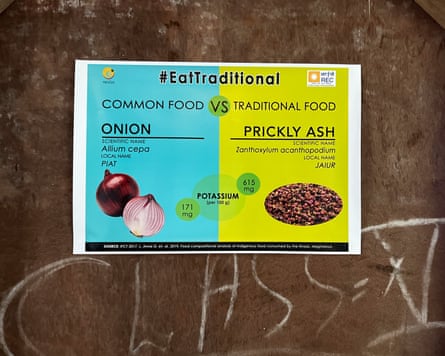

A months-long mapping exercise, conducted with community members, recorded more than 200 edible plant species across Meghalaya.

-

Kharmawphlang protects himself from the rain with a traditional bamboo rainshield as he inspects the school vegetable garden

-

Posters on classroom walls show the nutritional values of common foods and traditional alternatives. There are more than 200 types of edible plant across the state

These foods now form the basis of school menus, selected by committees comprising school staff, cooks, farmers, parents and headteachers, and supervised by Nesfas, who meet every month to plan meals.

A year into the project, an assessment conducted in schools that part of the initiative revealed that more than 92% of pupils were a healthy weight. This is especially significant in Meghalaya, which reports the highest rate of stunting in India: 47% among children under five, well above the national average and twice the rate of states such as Kerala.

At Laitsohpliah, Kharmawphlang says attendance has improved. And at the nearby Dewlieh government school, one of the teachers, Cheerfillius Khongngain, says he has observed a increase in pupils’ energy levels.

“The good part is that it supports both children’s nutrition and local farmers,” Khongngain says.

The reduced dependence on supply chains also means it is environmentally more sustainable and a community effort.

“These are no longer just school meals,” says Bada Nongkynrih of Nesfas. “They are community-led school meals – everyone is involved.”

-

Nine-year-old Ibansari Mawlong collects her food. The addition of foraged ingredients has transformed children’s appetites and energy levels

3 months ago

113

3 months ago

113