The actor Jack Shepherd, who has died aged 85, was, in his own quiet and modest way, a Renaissance man who not only acted beautifully on stage and screen for 60 years, but also wrote a dozen plays, directed at Shakespeare’s Globe, painted in oils, played jazz piano and saxophone, and loved singing.

His innumerable credits are testament to a pathological creative energy, and he was drawn most energetically of all to the contemporary writing of Trevor Griffiths and the National Theatre company of the director Bill Bryden in the Peter Hall era of the 1970s.

A television play by Griffiths, Through the Night (1975), starring Alison Steadman, was a harrowing hospital drama about the treatment of breast cancer, in which he played a doctor, and it prompted a national conversation in the press.

This was followed by the same author’s Bill Brand (1976), a series in 11 episodes in which Shepherd was the title character, a radical Labour MP caught in the crossfire of factionalism on the left (Arthur Lowe played a very Harold Wilson-like prime minister).

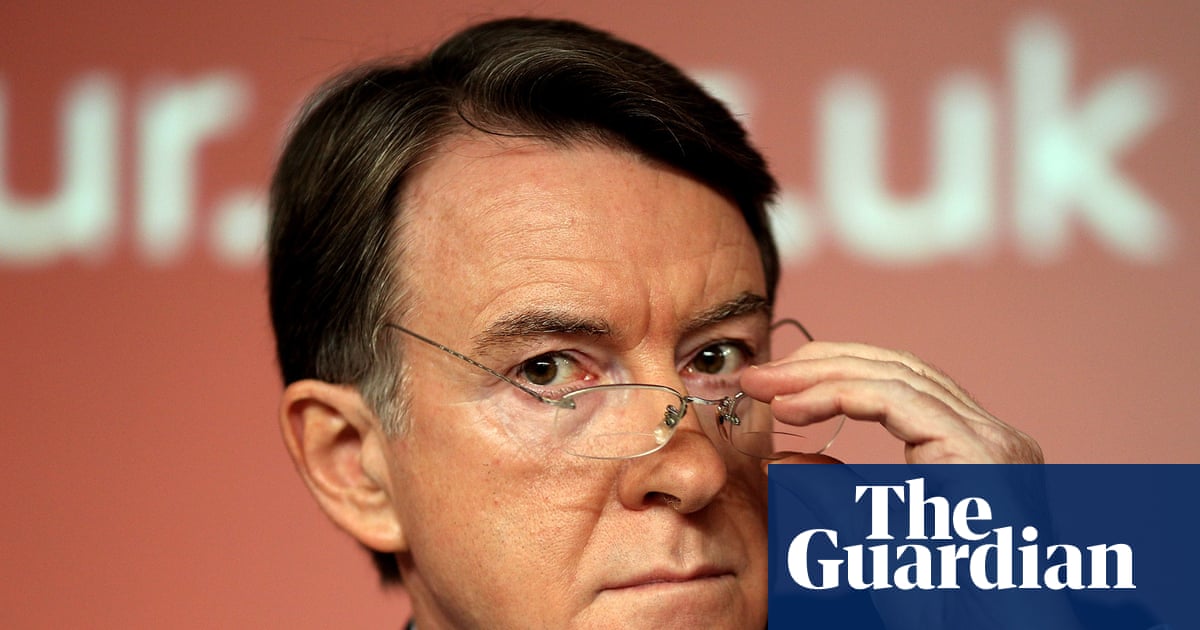

More recently, his profile was enhanced by the hugely successful TV drama Wycliffe (1993-98), in which he played DS Charles Wycliffe over five series and two 90-minute specials. The Cornish scenery was picturesque, the topographical detail exact and the subject matter covered not only violent crime, but the fishing industry and new age travellers.

In all this work, Shepherd was a model of low-key naturalism and intense concentration. You really could never see the joins in his acting; his inflections and changes of gear always perfectly judged, in a light tenor voice (though he sang as a baritone). Socially, too, he was low-key and resolutely non-partisan; his passion lay in the acting.

He was born in Leeds, the only child of Thomas Shepherd, a cabinetmaker, and his wife Violet (nee Hodgson), a teacher at an infant school. Jack was educated at Roundhay school in Leeds and King’s College, Newcastle (now Newcastle University), where he studied fine arts.

On graduating, he realised he wanted to be an actor and enrolled at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, before leaving with a breakaway group of teachers and students to form the more radical Drama Centre. He survived on money earned designing the sets for student productions.

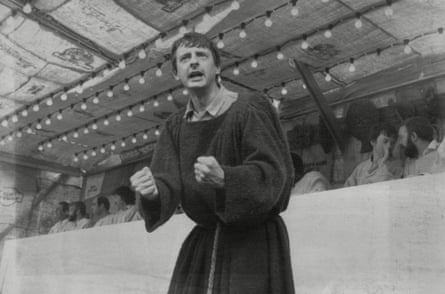

His professional debut came at the Royal Court in the 1966 season, where he appeared in John Arden’s Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance, in Arnold Wesker’s underrated Their Very Own and Golden City (with Ian McKellen) and, as a grotesque Mère Ubu opposite Max Wall’s Père Ubu, in Alfred Jarry’s surreal Ubu Roi, designed by David Hockney.

For the next five years Shepherd was a core member of the Court’s company, playing Solyony in Three Sisters (with Glenda Jackson and Marianne Faithfull), Malvolio in Twelfth Night, and key roles in two of Edward Bond’s best plays, The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Early Morning. He won a most promising actor award from the critics for the titular role in David Storey’s The Restoration of Arnold Middleton.

Shepherd returned to the Court in 1974 in David Hare’s Teeth ’n’ Smiles, about the implosion of a rock group at a Cambridge May Ball, opposite Helen Mirren. In the same year, he played in Hare’s revival of Griffiths’ The Party at the National – a superb analysis of fall-out and factionalism on the left – only a year after its premiere there with Laurence Olivier in his last stage role; Shepherd played, urgently and superbly, the part first taken by Frank Finlay.

In between he had been a founder member of the touring Actors’ Company formed by McKellen and Edward Petherbridge, playing Vasques in the Jacobean shocker ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore and a police inspector in a French farce, Ruling the Roost, in 1972; this was seen at the Edinburgh festival, where he returned in 1973 as Dracula in a play of that title that he co-wrote and took down south to the Bush.

A mark of Shepherd’s career was that he appeared – on stage and television – in the work of so many fine contemporary writers. Like Bill Nighy, he was not really an Elizabethan hose and ruff sort of performer.

On television with Griffiths he explored the dichotomy of political principle and compromise in Bill Brand, and All Good Men (1974); and in a stage play, Occupations (1971, televised in 1974), which anatomised the 1920 Fiat factory occupation refracted through the playwright’s response to the political climate after the 1968 protests in France.

At the National, as a linchpin member of Bryden’s company, he played in bristling American plays by David Mamet, notably the world premiere of Glengarry Glen Ross (1983), the best play about estate agents, for which Shepherd won a best actor Olivier (back then, a Society of West End Theatre, ie SWET, award) and, of course, the magnificent Mystery Plays trilogy by Tony Harrison.

The Mysteries started with The Nativity in 1977, followed by The Passion in 1980 and finally Doomsday, performed with the other two in 1985. The whole NT shebang was generously revived under Trevor Nunn in 1999, and Shepherd reprised his compelling, incisive portrayals of Lucifer, Judas and Satan.

On the way, he featured in a Peter Flannery mini-series (co-devised by Helena Kennedy) about the work of radical barristers, Blind Justice (1988), and later maintained his radical momentum in Peter Kosminsky’s Shoot to Kill (1990), which dramatised the events leading up to the Stalker inquiry concerning the killing of suspected terrorists by members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary; and in Paula Milne’s The Politician’s Husband (2013), in which he was an agitated politics professor father of David Tennant’s senior cabinet minister snared in a tangled marriage with Emily Watson.

He never broke through as a leading film actor, but he appeared in some good material, starting in 1969 as an underwater vicar in Richard Lester’s apocalyptic black comedy The Bed Sitting Room (based on a Spike Milligan play) and in Leslie Thomas’s The Virgin Soldiers, produced by Ned Sherrin.

He was in two notable Michael Winterbottom films – Wonderland (1999), a clever, striking, even (opined the New York Times) Chekhovian study, of three London sisters over a five-day period and the rather brilliant, bizarre A Cock and Bull Story (2005), based on Tristram Shandy, with Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon.

His plays included In Lambeth (at the Donmar in 1989), a riveting conversation about revolution between William Blake and Thomas Paine, with Blake’s wife holding the ring, and the ambitious Holding Fire! (at Shakespeare’s Globe, 2007) set against the rise and fall of the 19th-century Chartist movement.

Shepherd lived in later years with his second wife, Ann Scott, the television and film producer, in London and East Sussex, where he produced community stagings of Dorian Gray and Thomas Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree.

He was first married in 1965 to Judith Harland (they divorced in 1971), with whom he had two children, Jan and Jake, who survive him, as do Ann, whom he married in 1975, and their three children, twins Victoria and Catherine, and Ben. He is also survived by four grandchildren, Kit, Nora, Rose and Esme.

2 months ago

73

2 months ago

73