It’s a cloudy winter’s day in El Chañaral, an old Indigenous Wichi community now inhabited only by the Bustamante family. It lies nine miles from San José del Boquerón and near Piruaj Bajo, in Argentina’s northern Copo department.

As Batista Bustamante and Lidia Cuellar drink mate tea, their seven-year-old daughter, Marcela, climbs on to her purple bicycle and heads into the scrubland. She reaches a reservoir – a puddle of greenish-brown water – and pulls a pink pair of scissors from her pocket, which she drives into the earth to extract chunks of mud.

She gathers them in her hands and shapes them into cakes, plates and cups, as if preparing for a tea party. “Sometimes my bones hurt and I cry; here, here and here,” Marcela says, pointing to the joints in her hands and feet.

Through her mother’s side, she belongs to the Cuellar family, many of whom show symptoms of endemic regional chronic hydroarsenicism (Hacre), an illness caused by prolonged consumption of water with high arsenic levels.

In Argentina, the maximum permitted level of arsenic in drinking water is 0.01 milligrams per litre, as established by the Argentinian Food Code, in line with World Health Organization recommendations.

Yet according to an official report, the levels in the departments of Copo, Alberdi and some areas of Banda and Robles range between 0.4mg/l and 0.6mg/l. The most recent tests on her hair Cuellar underwent indicated she had a concentration of 2.24 micrograms per gram– or 224 times the legal level.

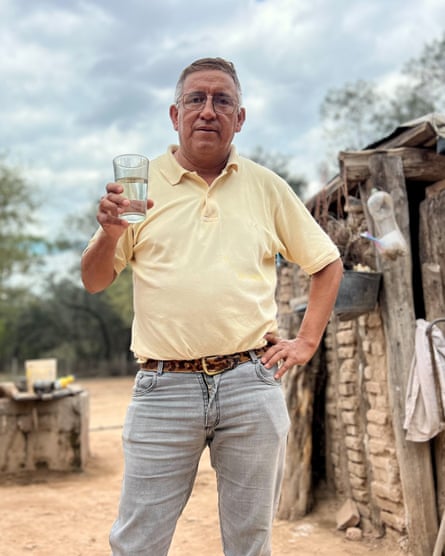

“You find a lot of that here,” says Santiago García Pintos, founder of Cynnal, a social development organisation working with rural communities.

“Some symptoms are quite identifiable,” he says. “You can see in children that they have hardened skin and develop freckle-like marks. In adults, it begins to crack and split, and that can lead to skin cancer. Teeth start to stain, and eventually, they fall out.

“Arsenic is known to cause kidney and liver cancer, and it’s suspected that many of the lung cancers we’ve had here in the area may have been related to that.”

Cuellar is a slender woman who always wears her hair tied back and speaks in a whisper. Following family tradition, she often drinks mate using rainwater collected from a cistern, as all of the water that comes from the ground – which they draw from wells as there is no piped water in such remote areas – is contaminated with arsenic and fluoride.

Although they depend on rainfall to stay safe, the combination of severe droughts and inadequate infrastructure for the scattered communities means they are often at the mercy of the state’s water tanker distribution system during the hot season, when their cistern runs dry.

When she was seven years old, Cuellar’s father died as a result of arsenic-contaminated water. “A water network is the most urgent thing we need,” she says.

She believes that drinking water contaminated with arsenic causes her recurring bone pain.

The last heavy rains were in April and the Bustamantes have only a quarter-tank of water left, which they draw out with a rope and bucket. For Cuellar, that is the only safe water.

“When it runs out, we have two options. Either we buy water from the commissioner, who draws it from the river – and God knows what’s in that – or we have no choice but to take water from the reservoir,” she says.

“All that water has arsenic. My family lived for many years in Vilmer, a community with high arsenic levels. My father developed sores, which burst open, and I think it was skin cancer. He and four of his siblings died of cancer. Erasmo, one of my uncles, is ill now.”

Cuellar also has symptoms. “It attacks my bones, and Marcela’s too,” she says. “We have to go for checkups once a year. We had them done recently. We have to go all the way to Santiago del Estero, and they cut our hair to measure it. I have the highest percentage, along with Marcela and a niece.”

According to Cuellar, the experts did not explain the consequences to their health of having those levels of arsenic in their systems.

Of 45.8 million Argentinians, about 4 million people live in areas with high concentrations of arsenic in the groundwater. However, more recent research from the National University of Rosario found there were 17 million people exposed to arsenic through water. Studies also indicate that up to 30% of patients with Hacre in Argentina develop cancer, especially of the skin and internal organs.

It remains a longstanding issue. In 2001 the Argentinian health ministry estimated that about one million people were exposed to it – or 3% of the population – mainly in Tucumán, Santa Fe, La Pampa and Santiago del Estero, where 100,000 people had symptoms of contamination.

In Argentina, arsenic contamination primarily occurs naturally through geochemical processes, with the element leaching from sources such as volcanic rocks into groundwater, rather than through industrial pollution or mining. Research is also exploring herbicides containing arsenic as a potential source of contamination.

Effective technologies exist to treat arsenic-rich water and are adaptable for municipal plants and household filters.

In November 2006, the Provincial Programme for Endemic Regional Chronic Hydroarsenicism was established to investigate and prevent arsenic, fluoride and other toxic chemical elements entering water sources.

“The province has developed policies to bring safe water to the towns and settlements most affected by arsenic and fluoride,” says Natividad Nassif, health minister of Santiago del Estero.

García Pintos disputes these claims. He lived in the area from 2018 to 2021 and has been travelling there regularly since then. “We really see how people live, and I can assure you that the government isn’t purifying water to remove arsenic in that region,” he says.

“There are no water networks or any treatment to make it fit for human consumption.”

As part of this programme, the ministry states that water and hair samples are regularly collected from San José del Boquerón, Piruaj Bajo and Vilmer for analysis.

Nassif says: “The health team is in contact with the Cuellar family, one of whose members presents symptoms compatible with Hacre and receives treatment at the Tránsito hospital in San José del Boquerón and at the dermatology centre of the health ministry” – a reference to Erasmo Cuellar, Lidia Cuellar’s uncle, who is undergoing treatment for skin cancer.

Erasmo Cuellar lives in Vilmer, one of the areas with the highest levels of arsenic in the water, and the effects on his health are clear: his hands are calloused and the skin on his back has white spots. His ears also have lesions.

“I drank that water from age four until about 20,” he says. “And my siblings drank it longer because they were older. There were eight of us, of whom only two are alive now. Seven of us fell ill with cancer and six have died. I’m managing the problem because it’s skin cancer that’s affected me.”

Marta Romero, Lidia Cuellar’s mother, moved several years ago to San José del Boquerón. She is now worried, because she has to go back to the city of Santiago del Estero for arsenic tests.

“Lidia’s father suffered from lymphatic cancer caused by arsenic. It started here on his leg, next to his groin, and then it spread throughout his entire body,” she says.

Romero says doctors told her that it was caused by arsenic poisoning. “That’s when the oncologist treating him told me I had to take all the children. I couldn’t just fold my arms watching the family die,” she says.

“I wanted to know at least if they can see what could be done. Losing someone you love and continuing with the same problem with your children is very hard.”

All tests carried out on the family were positive. “They all had it,” says Romero.

On a Monday morning, Marcela slings her rucksack on to her back and heads for school. She does not know how to write yet but has already learned to read by spelling out words. When she grows up, she wants to be a teacher.

Cuellar still does not take Marcela for regular health checkups. “Sometimes, when doctors come to the school in Piruaj, I take the opportunity to have a paediatrician see her. I want someone to examine her about the bone pain,” she says.

Although the health problem is severe, her family has another priority. In the morning, Cuellar prepares a chicken and pasta stew for lunch. This time, they have enough food – but that is not always the case. “Sometimes,” she says, “there is nothing to eat.”

-

This report is a partnership with the Argentinian newspaper La Nación. Read it here in Spanish

2 months ago

77

2 months ago

77